Taxonomy is a scientific system that sorts organisms into related groups. Complex and precise, this classification narrows something from its place in a broad category down through ever-more-exacting descriptions. For example, it distinguishes the physical characteristics of, let’s say, squirrels from opossums and daisies from turnips.

Taxonomy isn’t static, it routinely undergoes challenges and upheavals as new technological capabilities, such as DNA analysis, keep taxonomists reclassifying and rearranging species. Not only that but new species are discovered all the time, adding to a system that’s already enormous—currently, about 1.8 million species.

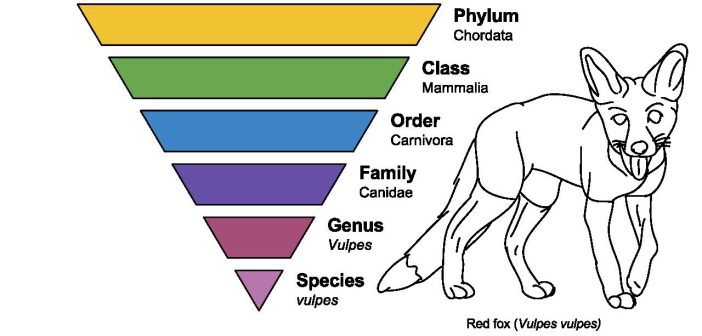

At the top of this page is the basic hierarchical classification of the Red Fox. What isn’t shown are the many intermediate levels that lead to a description that fits a Red Fox and only a Red Fox. You’ll see its complete classification below.

Notice the hierarchy begins with the broadest category, Domain, which includes virtually every living thing in the world. The description gets more specific at each subsequent level, called a taxon (plural: taxa). This fox’s scientific name is the last two taxa: genus and species. Only the Red Fox, Vulpes vulpes, meets every description from top to bottom. There are other foxes, such as the Kit Fox, Vulpes macrotis, and Arctic Fox, Vulpes lagopus, but they don’t fit the Vulpes vulpes description precisely. Their scientific classifications are slightly different from the Red Fox, as well as from each other.

Scientific classification: Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) (Linnaeus, 1758)

| Domain: | Eukaryote (cells with membrane-bound nucleus – humans, plants, etc.) |

| Kingdom: | Animalia (animals: multi-cellular, must eat for energy) |

| Eumetazoa: | Metazoans (having germ layers, neurons, embryonic gestation); Bilateria: bilaterally symmetrical animals |

| Deuterostomia: | Deuterostomes (distinguishing sequence of embryonic development) |

| Phylum: | Chordata (notochord, dorsal hollow nerve cord, pharyngeal slits) |

| Craniata: | Craniates (vertebral column and bony vertebrae) |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata (vertebrates: vertebrae during embryonic period) |

| Superclass: | Gnathostomata (jawed vertebrates) |

| Euteleostomi: | Bony vertebrates |

| Class: | Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fishes and terrestrial vertebrates) |

| Tetrapoda: | Tetrapods (tetrapods: four legs) |

| Amniota: | Amniotes: embryo develops within a protective membrane) |

| Synapsida: | Synapsids: bony arch behind each eye) |

| Class: | Mammalia (mammary glands, hair, diaphragm) |

| Subclass: | Theria (Therian mammals: give birth to live young) |

| Infraclass: | Eutheria (placental mammals) |

| Order: | Carnivora (carnivores: eat meat) |

| Suborder: | Caniformia (caniform carnivores: long jaw, nonretractile claws) |

| Family: | Canidae (coyotes, dogs, foxes, jackals, wolves) |

| Genus: | Vulpes (smaller size, flatter skull, pelt markings and colors) |

| Species: | vulpes (pelt color, markings) = Red Fox |

Naming rules

Modern scientific classification was designed by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), a Swedish botanist and physician who loved nature. Called the Father of Taxonomy, he named and classified several thousand species during his lifetime.

Formal international agreements hold tons of rules for naming species. One of them concerns the “discoverer” and the year of its classification. For example, Linnaeus was the first to classify the Red Fox, so you’ll often see it listed this way: Vulpes vulpes (Linnaeus, 1758). It occasionally happens that two or more individuals, unbeknownst to each other, have given different names to the same species. In that case, only the first describer is recognized.

Scientists use “binomial nomenclature” to name each life-form on our planet. This simply means they use two words for a name—the genus and species, always in that order. Think of it as equivalent to a person’s last name, followed by their first name. Again using the Red Fox, there are many foxes with the “last name” of Vulpes, but only one that also has the “first name” of vulpes. A clearer example might be tree squirrels. They all have the “last name” (genus) of Sciurus, but only the Fox Squirrel has the “first name” (species) of niger. There is an exception to the two-name rule, which occurs when referring to a subspecies—then three names are allowed, such as Homo sapiens sapiens.

Why Latin?

You’ve undoubtedly noticed that scientific names are always in Latin, hard to decipher, and hard to pronounce unless you speak it (even then, scientists differ in pronunciation). However, this custom serves an essential purpose as it avoids confusion between speakers of different languages. For example, in Spanish, the common name for “Red Fox” is Zorro rojo; in German, it’s roter Fuchs; and in French it’s Renard rouge. Yet, every scientist in the world knows which animal this is by its Latin name, Vulpes vulpes.

Just for fun, here’s another classification, this time using humans, because we can easily relate to the physical descriptions that separate us from other animals at each level.