Last updated: November 20, 2023

Right now, there are 150,300 animals and plants in danger of extinction.

We humans can adjust to changes in our environment rapidly. If we should be forced out of our lodging or off our land, most of us could move to another place that suits us. We immediately know what possibilities are in the next neighborhood over, across town, or even in another state. We’d know where grocery stores are, full of food and beverages. And, because of automobiles, we could get there fast. Under ordinary circumstances, we can quickly locate retailers of everything we need for survival, even in an unfamiliar city.

But, what of wildlife? When the habitat wildlife is adapted to disappears, where can they go? Except for birds and other flying animals, imagine the challenge of relocating to a suitable place when your visual vantage point is only three feet (1 m) above the ground, like that of a fox. Or, chipmunk height, just a few inches. Which direction should they go? Can they find food before they starve? Or a safe place to rest? And water—where’s water? The place they were forced from was completely familiar: The best hiding spot was under the old log behind the bushes. The creek was just around the bend to the left. Food was on the ground under the fruit trees that stood behind the small forest of pine trees on the other side of the hill.

Some wildlife can’t adapt

Some animals manage to find suitable new locations. Others are capable of adapting to a new way of life, as the Northern Raccoon and Virginia Opossum have done very well within cities. But, it can be tragic when an animal never finds its way to safety and sustenance. Or they can’t adjust because their instincts and needs are so unalterable they can’t substitute, say, a forest of pines for a woodland of deciduous trees. Some bird species won’t breed except in a specific habitat—when their perfect habitat is destroyed, one by one, they die off. The Last Dusky Seaside Sparrow

Root cause of habitat loss

What’s at the root of habitat loss? Urbanization and development, timber cutting, agriculture, and fragmentation by roads and reservoirs. Native ecosystems, which developed their delicate balance over eons, are disappearing at an estimated 6,000 acres per day in the United States as they’re dredged, drained, cleared, paved over, built upon, or otherwise made uninhabitable for much of its historical wildlife.

Regarding the international impact of habitat loss, Wired.com makes this strong statement: “…humans are Earth’s great omnivore, and our omnivorous nature can only be understood at global scales. Scientists estimate that 83 percent of the terrestrial biosphere is under direct human influence. Crops cover some 12 percent of Earth’s land surface and account for more than one-third of terrestrial biomass. One-third of all available freshwater is diverted to human use.

“Altogether, roughly 20 percent of Earth’s net terrestrial primary production, the sheer volume of life produced on land on this planet every year, is harvested for human purposes—and, to return to the comparative factoids, it’s all for a species that accounts for .00018 percent of Earth’s non-marine biomass.”1

Threatened and endangered species in the United States

The highly respected International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists more than 1,3002 animal and plant species as threatened or endangered in the U.S., meaning they’re now so rare as to become extinct. There are seventy-seven birds, including some species of warblers, terns, thrush, vireos, quail, the Whooping Crane, Bald Eagle, and California Condor. Sixty mammals are on the list, including species or subspecies of wolves, foxes, squirrels, bats, rabbits, skunks, deer, caribou, pumas, jaguars, whales, seals, and the Florida Panther, Ocelot, and West Indian Manatee. Ninety-three species of reptiles and amphibians are there, along with about 200 invertebrates, including butterflies, snails, insects, spiders, worms, and others. One hundred sixty-three marine species are on it, too. The tally for plants is 947, with 903 being flowering species.

Worldwide, the number of threatened or endangered species on the IUCN list is staggering: more than 150,300, representing 41 percent of all amphibians, 37 percent of sharks and rays, 36 percent of reef-building corals, 27 percent of mammals, 25 percent of birds, and 34 percent of conifers.3

A state’s eye view

Here’s a quick look at some state statistics. As of 2023, California has 305 threatened or endangered animal species, Florida has 166, and Texas has 95. Kansas has thirty-one, New York has ninety-one, Oregon has eighty-four, and Arizona has fifty-eight. (However, it’s important to note that these numbers may have changed since then due to various factors such as conservation efforts or changes in population size.) You can find a list of the endangered species in your state or county here.

A few of the endangered wildlife and plants:

Attwater’s Prairie Chicken

The Attwater’s Prairie Chicken, Tympanuchus cupido Atwater, a ground-dwelling grouse, is nearly extinct due to the conversion of its coastal tallgrass prairie environment into farmland. Less than a hundred years ago, one million of these birds inhabited six million acres in Texas and Louisiana. Avid hunters competed to kill the most per day while land conversion was destroying their habitat acre-by-acre. Eventually, it was almost gone, and by 1919, in Louisiana, so were all the Attwater’s. In neighboring Texas, by 1937, their population was down to just 8,700 individuals.

Less than one percent of the original habitat remains. In 2016, there were thirty-two in the wild, and the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) had twenty-nine in a captive breeding program when Hurricane Harvey wiped out all but five of the birds. Soon after, two more went missing. The only good news is that a few zoos have small populations of their own, and the USFWS, in cooperation with The Nature Conservancy Texas, has helped increase the wild population to nearly two hundred since the hurricane.

Ocelot

The Ocelot, Leopardus pardalis, is a spotted and striped wildcat native to the Southwest, as well as Mexico and regions farther south. It’s endangered in the U.S. because of the loss of sub-tropical woodlands it calls home. What was once three million acres of coastal prairies and chaparral thickets has been reduced by 95 percent. Originally numbering an estimated 800,000 to 1.5 million in the Western Hemisphere, now only fifty remain in the wild. Most live on the 45,000-acre Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge near Bayview, Texas.

Territorial animals, young Ocelots go in search of a suitable territory of their own when they leave their mothers at about one year of age. Unfortunately, every year, several of them are hit by cars as they cross roads within the refuge. The Ocelot requires a very wild, naturalized environment to survive, and most of the area around the refuge has been stripped of vegetation. There’s no place else for them to go.

Whooping Crane

The Whooping Crane, Grus Americana, is another tale of a large population that fell precipitously because of habitat destruction and overhunting. Fossil evidence shows that it dates back several million years and lived across the entire eastern half of the U.S., north into Canada, and south into Mexico. Whooping Cranes summer in Canada and winter in Texas, migrating 2,500 miles each way. During migration, which takes several weeks, they face weather hardships, illegal shooting, power lines, cell phone towers, predators, disease, and the continuing destruction and pollution of their summer and winter stopping grounds.

By the 1890s, most Whooping Cranes had been killed or driven away from their marshy grassland habitats, and the last nesting pair in the U.S. was seen in 1939. By 1941, sixteen birds were left, and by 1950, the Whooping Crane was extinct in the U.S. With that, the USFWS began a captive breeding program, along with Federal protection of designated habitats. It has taken fifty years to bring their wild population to 300 today.

Black-footed Ferret

The Black-footed Ferret, Mustela nigripes, North America’s only native ferret species, is one of our most endangered mammals. Considered globally extinct in 1987, a group of seven was discovered in Wyoming in 1991. Since then, a USFWS captive breeding program, along with efforts by numerous groups, such as local agencies, Native American tribes, conservation groups, and others, has given them a second chance for survival.

They remain fragile, however. Their primary prey, Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, have been eradicated by landowners and government-sponsored poisoning programs to near extinction, with only 2 percent of their population remaining. Additionally, less than 2 percent of the ferret’s prairie habitat remains and is highly fragmented. This has resulted in a wide dispersal of the prairie dog towns, making it difficult for the ferrets to find them.

Red Wolves

Red Wolves, Canis rufus, beautiful carnivores once common throughout the southeastern U.S., were down to seventeen individuals by the 1980s due to habitat loss and comprehensive predator eradication programs. USFWS captured the remaining wolves and began a captive breeding program.

As of October 2023, there are twenty to twenty-two Red Wolves in the wild, inhabiting a small area of North Carolina, mostly in protected areas. Another 267 are held in captive breeding facilities across the U.S. Without these safeguards, Red Wolves living in the wild will become history. Private landowners resist Federal efforts to release Red Wolves.

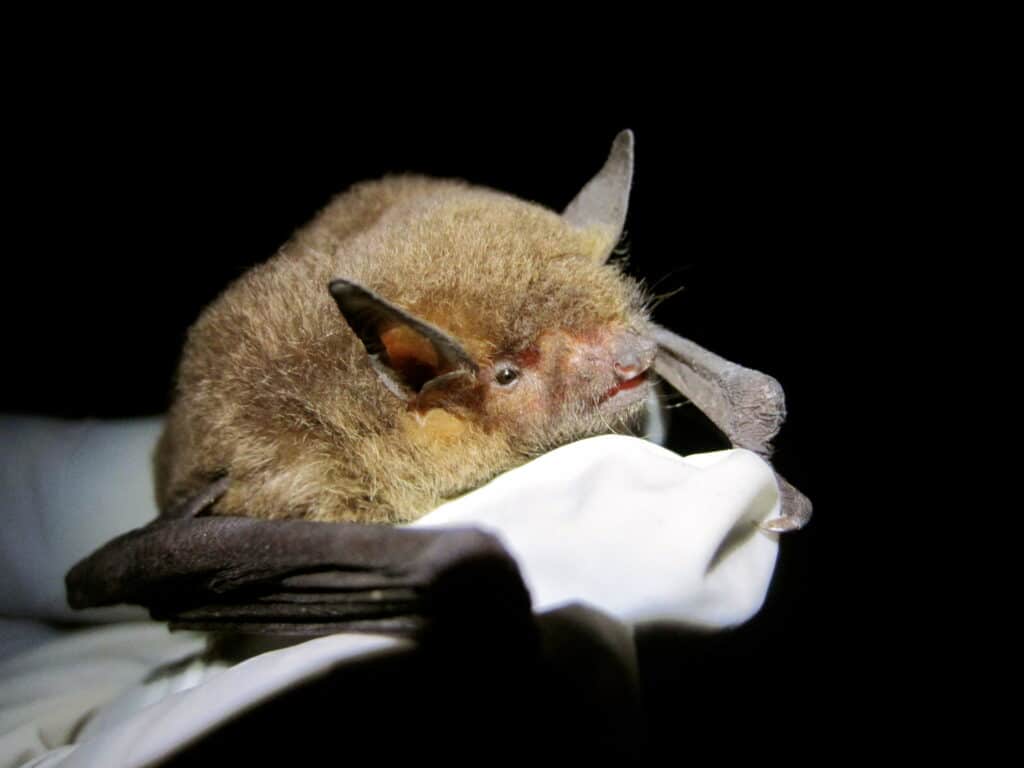

Gray Bats

The Gray Bat, Myotis grisescens, a cave-dweller, is endangered across its range, which includes Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and nine other states. The primary threat to their existence is human encroachment.

In 1996, when the Gray Bat was federally listed as endangered, the population stood at approximately two million. By 2000, there was an alarming 50 percent decline, with most losses occurring in the latter part of the twentieth century. Notably, ninety-five percent of Gray Bats hibernate in just fifteen caves. The opening of many caves to the public resulted in issues such as excessive harassment, loss of young bats, and disturbances from cave exploration, particularly during hibernation. Dam-building activities also led to flooding.

Since then, positive strides have been made through collaborative efforts from voluntary landowners, stewardship plans, conservation easements, and other initiatives. Fourteen hibernacula are now under permanent protection, and 76 percent of their summer roosting places are secured. It’s crucial to recognize that a disturbance in even just one cave can significantly impact thousands of bats simultaneously.

Other wildlife

In the U.S., there are 165 species of threatened and endangered fish, including some species of salmon and whales. They’re suffering from pollution, climate change, blockage of migration, negative consequences of water management, and, in some cases, non-native species that have been introduced and are decimating native fish populations.

On a worldwide basis, 90 percent of all large ocean fish are gone, resulting from habitat damage and overfishing. TheWorldCounts.com, which amasses data from the world’s foremost organizations, predicts that by 2048, there will be no more fish in the oceans. Nations, aware of this, have moved to curb the decline through fishing restrictions, but considerable illegal fishing continues, and it appears to be an uphill fight.

The Northern Red-bellied Cooter, Pseudemys rubriventrisan, is endangered due to habitat loss and fragmentation caused by human development. (cuatrok77 / Flickr; CC BY-SA 2.0)

Scientists warn us that the complete loss of too many species, or even a drastic reduction in their populations, may have an unforeseen disastrous effect on humans later. Earth has had numerous extinction events, both large and small, during the hundreds of millions of years since life first appeared.

The Karner Blue Butterfly is endangered due to habitat loss and modifications. (Justin Meissen / Flickr; CC BY-SA 2.0)

But, always before, there was intervening time for it to recover its biodiversity. On a moral level, there’s also the issue of whether it’s right to wipe out other species because they inconvenience humans or for sport.

Plants are crying out, too

Plants don’t have the tragic aura of animals, especially when they’re milkweeds, clover, and orchids, but globally, of 63,306 assessed plant species on the IUCN Red List, 25,208 (40 percent) are threatened or endangered. At highest risk are 14 percent of rose species, 32 percent of lilies, 32 percent of irises, 14 percent of cherry species, and 29 percent of palms. The U.S. has more species of plants threatened with extinction than any other country—947.

The Dwarf Bear-Poppy, Arctomecon humilis, inhabits small areas in Utah, including cities; endangered due to habitat loss. (Andrey Zharkikh / Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

How did this happen? In much the same way humans have impacted animals—the conversion of wilderness to agricultural land, development, logging, and the unwise introduction of alien species that crowd out native species.

Think about how vital plant life is to humans. Some 3,000 species of plants are used for food. Of the top 150 medicines today, eighty-seven are based on plants. Experts believe that genes from even more of them may lead to the medicines of tomorrow—but only if they’re still around. Plants have industrial importance, too: they provide fibers for clothing, wood for building and burning, and fuel, such as corn ethanol and soy diesel.

White Prairie Fringed Orchid, Platanthera praeclara, threatened due to habitat conversion to farmland, overgrazing, intensive mowing, water drainage, competition from introduced species, and herbicides. (Justin Meissen / Flickr; CC BY-SA 3.0)

Plants also provide oxygen through photosynthesis, their foliage traps dust and pollutants, and they intake carbon dioxide, which helps lessen the greenhouse effect. They control erosion. And, of course, they provide food, hiding and nesting places for wildlife. Water plants provide cover and habitat for spawning fish and help filter sediments to keep water clean.

A host plant for Monarch Butterflies, Mead’s Milkweed, Asclepias meadii, is threatened or endangered throughout its range by habitat loss and herbicides. (Jay Sturner / Flickr; cc by 2.0)

The aesthetic value of plants would also be a loss: who hasn’t been awed by the beauty of a field of wildflowers, of tropical foliage nestled under a canopy of majestic trees draped with moss, of grasses waving in a soft breeze, or even a precisely symmetrical formal garden.

Going, going…

Two out of every five known species on Earth face extinction in the foreseeable future. This includes one in eight birds, one in four mammals, and one in three amphibians. In total, 784 species have become extinct since record-keeping began.

We can ensure that plants and animals stop disappearing as a result of human actions through communal, concerted effort. Many expert groups around the world are trying. We can personally help slow the extinction rate by doing what we can, where we can. Donate time and money to conservation groups; contact political leaders and influential businesspeople; and create backyard wildlife habitats where, under our own stewardship, wildlife and native plants will be safe.

REST IN PEACE

Just since 1975, nineteen species of birds have become extinct, bringing the total of extinct birds to eighty since 1900. The most recent, in 2004, is the Po’ouli, a Hawaiian species. Extinction obituary3

Hawaiian Po’ouli (or Black-faced Honeycreeper), Melamprosops phaeosoma (Paul E. Baker / USFWS; P.D.)

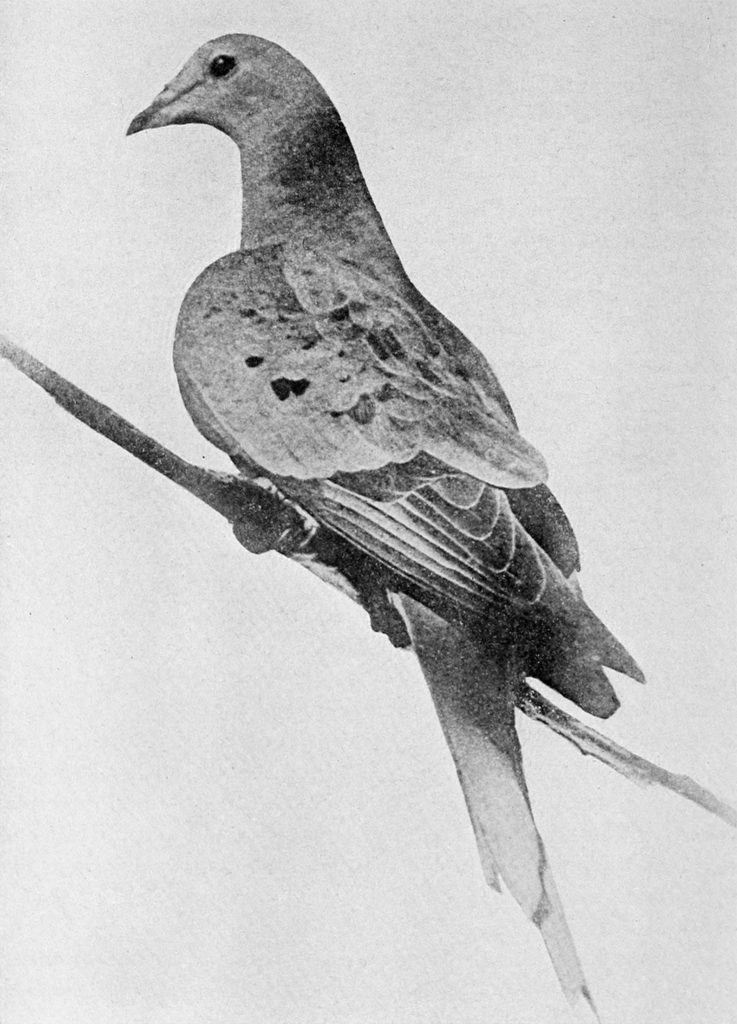

Passenger Pigeon

No extinction has been more dramatic than that of the Passenger Pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius. When Europeans first arrived in N.A., an estimated three billion to five billion Passenger Pigeons blanketed the continent, so many they darkened the skies, and John James Audubon, the famous naturalist, wrote of watching a flock in 1813 that passed overhead for three whole days.

It seems inconceivable that such an enormous population could go extinct, but the forests they depended on for nuts and berries were turned into farmland, and the pigeons were killed for food and their feathers. And, most particularly, for sport—hunters would fill wagonloads of Passenger Pigeons during organized shoots for no other reason than to kill as many as they could.

The last wild one was shot in Ohio in 1900. The only remaining Passenger Pigeon, a captive named “Martha,” died in 1914. She was named after President George Washington’s wife.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker

The Ivory-billed woodpecker, Campephilus principals, had been considered extinct for sixty years due to the destruction of most of the forests it lived in until April 2004, when one—just one—was reportedly seen in a deeply forested area of Arkansas.

This Ivory-billed Woodpecker photo was taken in 1935 by Arthur A. Allen and colorized by Jerry A. Payne, USDA Forestry Service; CC BY 3.0)

Extensive organized searches in the area since then have turned up nothing, and the sighting is now considered by most to have been a misidentification of a similar woodpecker.

Dusky Seaside Sparrow

The saga of the Dusky Seaside Sparrow, Ammodramus maritimus nigrescens, is another heartbreaking tale of thoughtless human actions. The Dusky was a black-and-white shorebird that lived exclusively on the central Atlantic coast of Florida and on Merritt Island, which is situated just off the coast, between Cocoa and Cocoa Beach, Florida. The Dusky nested on cordgrass, Spartina bakerii, which required a very specific habitat in order to grow—wet, but not too wet.

The last Dusky Seaside Sparrow, Ammodramus maritimus nigrescens, was called Orange Band. When he died on June 17, 1987, his species became extinct. (USFWS; CC)

In 1963, the nearby Kennedy Space Center attempted to control a mosquito-breeding problem by flooding the sparrows’ marsh without trying to preserve habitat for any of the species that depended on it. This action, along with the use of the insecticide DDT, effectively destroyed the population of Dusky Seaside Sparrows.

But then, seemingly good news: another population of the sparrows was discovered in a different marsh growing cordgrass. This time, concerned parties convinced the USFWS to purchase and protect the land as a nature reserve. But, recklessly, the Florida Department of Transportation was allowed to build a highway through the reserve as a connection from Disney World to the Kennedy Space Center, and, ultimately, the last of the marsh was drained for real estate purposes.

The Dusky had no place left to go. A belated effort was made in the mid-70s to turn part of the area back into a marsh, but it proved to be too late for the little sparrows. In 1979 and 1980, five remaining Dusky Seaside sparrows, all males, were captured and introduced into a crossbreeding program with a similar species. The program eventually failed, and through the years, one by one, the birds died. The last Dusky, called “Orange Band,” died in 1987.

| Listen to a Dusky’s call |

| More about the Dusky |

| Robert James Waller’s essay on Orange Band |

“Biodiversity can’t be maintained by protecting a few species in a zoo, or by preserving greenbelts or national parks. To function properly, nature needs more room than that. It can maintain itself, however, without human expense, without zookeepers, park rangers, foresters or gene banks. All it needs is to be left alone.” – Donella Meadows, environmental scientist and writer

| 1 Brandon Keim, “Making Sense of 7 Billion People,” Wired.com, October 21, 2011. |

| 2 Source: the widely respected International Union for the Conservation of Nature “Red List,” as of 2023, https://bit.ly/49LHbsr. |

| 3 Helen Sullivan, “Extinction obituary: why experts weep for the quiet and beautiful Hawaiian po’ouli,” TheGuardian.com, May 4, 2022, https://bit.ly/46vei0X. |