To most people, skunks are dumb, ill-tempered animals best known as stinky roadkill and good riddance. A shame because that’s based on not knowing anything about them: you’ll find when you read all about striped skunks that they’re docile, non-aggressive, and perfectly happy to leave humans alone and go quietly about their lives.

There are four groups (genera) of skunks in the United States1. The most common are Striped Skunks, Mephitis mephitis, composed of thirteen subspecies. One or another of them can be found across the United States, up into southern Canada, and down to the northern border of Mexico. Their natural habitat is both open areas and areas bordered by forests, grasslands, and agricultural lands. It should come as no surprise, then, that urban yards are enticing—lots of clipped grass dotted with islands and borders of shade trees and shrubs. So you may very well have them visiting your yard at night, and it’s important to know that’s a good thing: skunks play a beneficial role as predators of pests, such as grubs, snails, slugs, beetles, wasps, ants, millipedes, centipedes, small snakes, mice, and rats, among others.

Background

It’s thought that skunks initially crossed from Siberia into Canada on a landbridge in ancient times before the two continents became covered by water, which separated them (as it still does). The oldest skunk fossil, found in Germany, dates back to 11 to 12 million years ago, in the Miocene Epoch. However, genetic evidence shows they originated much earlier, 30 million to 40 million years ago, in the Early-Eocene to Late-Paleocene Epochs. Initially, skunks were thought to be badgers, and they did share an ancestor, but later evidence indicated they more accurately belonged in a separate family, Mephitidae, along with stink badgers, 2 their closest relatives. The oldest evidence of skunks in North America, a skull fossil believed to be 9.2 million to 9.3 million years old, was found in the Mojave Desert’s Red Rock Canyon.

When German naturalist I.C.D. von Schreber gave the Striped Skunk its Latin name in 1776, he chose the word Mephitis for both its genus and species, apparently meaning to give that word the power of two! It would be hard for anyone who has smelled skunk spray to argue against his reasoning because Mephitis (muh-FIE-tiss) is Latin for “a noxious, pestilential, or foul exhalation from the earth.” 3

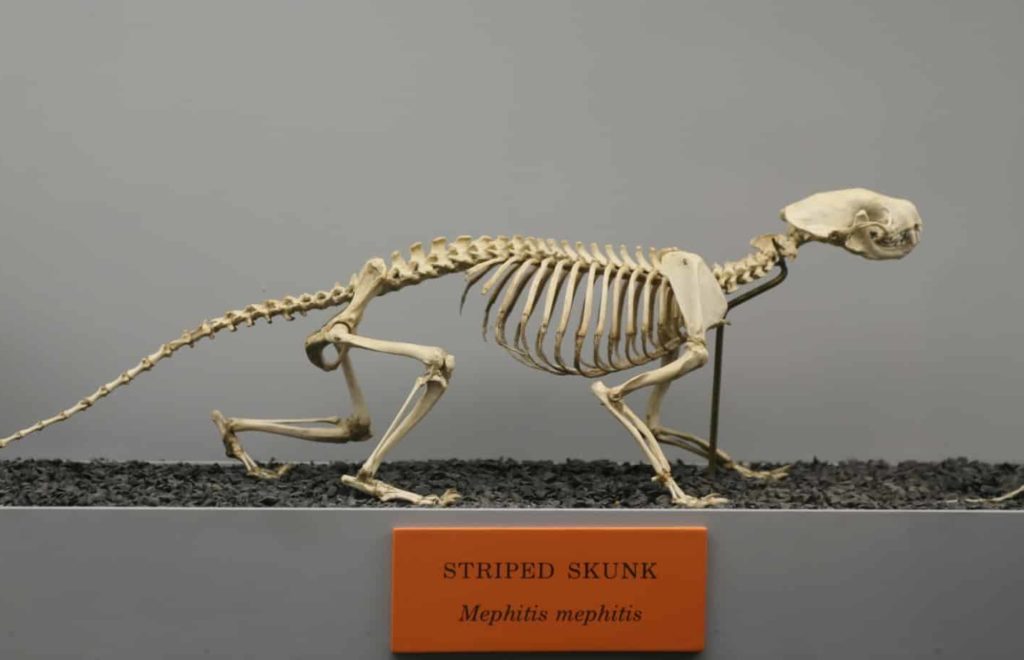

Physical description

The body of Striped Skunks is 13–20 inches long (33–50.8 cm), plus a tail length of 7–10 inches (17.8–25.4 cm). Males are slightly larger than females. Their weight averages 6.0–8.0 pounds (2.7–3.6 kg) but can go up to 15 pounds (6.8 kg).

Striped Skunks have a triangle-shaped head with a black nose and short ears. The hair is black, with two broad, white stripes running from the back of the head to the tail, which is a bushy mix of black and white hairs. In addition, a thin white stripe runs from their forehead to their nose. The stark contrast between white and black is very noticeable and warns predators to stay away. Their legs are short, and their feet have long, curved, strong claws—especially the front ones, used for digging.

Ewww, the stench!

Effective, isn’t it? If you’ve smelled it, you don’t forget it, and you’ll stay away! Humans can detect it in a concentration of ten parts per billion, which is why we can smell it from long distances. The spray is a mix of seven smelly sulfur-containing compounds called thiols and thioacetates, which effectively drive predators away. It comes from two glands, one on each side of the anus, and skunks can spray it separately or simultaneously as a defense.

Although skunks are best known for their spray, they use it only as a last resort. For one thing, they’re docile by nature and like to avoid confrontation. But there’s another issue at play, a critical one: The supply of spray they have “onboard,” so to speak, measures only about one tablespoonful (15 ml) divided between the two glands. That’s enough for five or six effective squirts—but it’s the skunk’s only means of defense, and it takes about ten days to replace it entirely. They’ll try to defend themselves by biting and scratching, but spraying is their best protection from predators.

They’ll warn you

Given a chance, a skunk will warn predators and humans away before blasting them. It’ll growl and hiss, stomp its feet, arch its back, chitter, and pretend to charge forward. It may do this several times, and you shouldn’t still be standing there! Back away slowly and quietly. If it starts to turn its back on you—RUN! Because the result is even worse than the smell: The liquid causes eyes to sting fiercely, temporarily blinding the foe (human or otherwise). It burns the skin. It can cause nausea. The odor clings to everything it touches, refusing to be rubbed or licked off. It’s no surprise that a critter won’t intentionally harass a skunk ever again!

Animals, and humans, too, usually get sprayed because they’ve come suddenly upon a skunk and startled it. If skunks are known to inhabit your area, always use a flashlight when stepping outside at night. It will alert both you and a skunk of each other’s presence.

Senses

Skunks have poor vision, with objects going fuzzy about 10 feet away (3 m). So, they rely on their senses of smell, hearing, and touch.

Intelligence

Striped Skunks are intelligent. Very. That’s what owners of pet skunks say, and research backs them up. They learn quickly and have a good memory. Owners describe them as determined, curious, and so ingenious that baby locks sometimes have to be put on cupboards and drawers to keep them out. Some can even open refrigerators. They’re friendly, playful, bond with their human companions, and like to cuddle. They can also be litter box trained. Watch a playful skunk and puppy: https://bit.ly/1iGGfKG

Communication

Striped Skunks aren’t particularly vocal but make a few sounds. They hiss, growl, squeal, and coo, as well as other noises that are hard to describe.

Behavior

Skunks are nocturnal and typically rest in their dens by day. Not always, though—it isn’t uncommon for them to forage in the daytime, especially nursing mothers, who are extra hungry. And their youngsters often come out to play. Here’s one playing with a human (but don’t try this yourself!): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLz1GSkJeks

Skunks live solitary lives except during mating season, which is late winter to early spring. Males are particularly active during this time as they search for females. They sometimes fight over females but don’t spray each other.

Skunks can climb fences and other obstacles, but not well, and they don’t climb trees. They would rather walk than run, but their short legs can move them in bursts of 4 to 6 miles per hour (6.4–9.7 km/h), if necessary. They also can swim.

Torpor

In the fall, they begin packing on fat. The extra fat allows them to stay in their dens for days or weeks in the winter, “sleeping” in a physical state called torpor. During torpor, their body temperature and metabolism rate decrease, but it isn’t as deep as true hibernation. Striped Skunks reach the lowest torpid body temperature of all carnivores, dropping from 98.6°F to 78.8°F (37°C to 26°C).

Reproduction

The males can breed at about ten months of age, and the females around eleven months. Late winter to early spring is the mating season. Males go their way afterward and don’t participate in rearing their offspring.

Females give birth about two months later, typically to five to seven babies, although ten is possible. At birth, the kits weigh about one ounce (28.3 gm) and are blind, deaf, scantily furred, and have barely detectable white stripes.

At eight days, they begin producing musk; at about three weeks, their eyes open; at six weeks, they start hunting with their mother. She teaches them all her skills. Such things as how to dig up grubs and extract larvae from logs, raid beehives and locate rodents, root around for eggs and insects, and sort through garbage for edibles.

Sometimes a mother will be seen with her kits waddling single file behind her, out for a stroll, identical miniature versions. They look adorable, but this is one time a skunk is definitely not to be messed with—protective of her young, the mother might forego her usual warning and immediately spray.

The playful and curious kits are nearly grown at eight weeks but often stay with their mother over the winter. In the spring, the young males usually wander to a different area, while females tend to remain close to their mothers. Dispersed skunks from the same litter who later meet up are said to be overjoyed at seeing each other again. The mother can breed a second time in the same year but usually doesn’t unless her first pregnancy fails.

Nesting

Striped Skunks use dens year-round. They’re located in well-protected places, such as culverts, rock piles, and woodpiles, in or under hollow logs, under porches and sheds, and in crawl spaces or drainpipes. If they find a den abandoned by another animal, they’ll use it.

They dig a den of their own only if they must. It may have as many as five entrances, and nesting materials include soft twigs, grasses, and leaves. They keep themselves clean and are careful not to spray within it. Still, skunks always have a slightly skunky smell, so their dens do, too.

Food sources

Skunks are omnivores and opportunists—they eat whatever they find or can catch. Their foraging helps to keep mice, rats, and shrews under control, as well as nuisance insects—grubs, grasshoppers, bees, wasps, crickets, and caterpillars, for example. They also feed on fish, frogs, salamanders, turtle eggs, eggs of ground-nesting birds, young rabbits, small snakes, leftover pet food, and birdseed. They might top off a meal with grasses or nuts. A fruit salad in season is another delight for them, made up of fallen, spoiling fruit, such as blackberries, blueberries, and cherries.

Lifespan

The average lifespan of the Striped Skunk is about two years in the wild. Many die of starvation in their first winter, and disease also takes a toll. In captivity, they can live up to fifteen years.

The next time you see a skunk lying on the side of a road, you’ll know it isn’t better off dead. If it’s a mother raising offspring, her young may starve to death or have now lost their teacher of life-saving skills. To her litter mates, she’s a lost playmate who squealed with joy whenever they reunited. And nature has lost an important predator.

Predators

Skunks have few predators, except human ones driving vehicles (the most common cause of their death) and those who intentionally kill them as pests. Their only other serious predator is the Great-horned Owl, which seems impervious to the foul odor, but there’s also some predation from Mountain Lions, foxes, and hawks.

Striped Skunks and rabies

Rabies is a deadly disease, and skunks are more prone than some other mammals to get it. Still, only 846 tested skunks were found to be infected with rabies in 2020, according to the most recent report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most of them were in five states: Texas, North Carolina, Virginia, Arizona, and Georgia. This statistic dramatically illustrates that the number of infected skunks is quite low within a population of animals that inhabits the entire country. Still, should you get bitten or scratched, immediately go to your doctor for rabies shots, the only thing that can save you if the skunk was rabid. The shots are no more painful than flu shots.

Don’t assume, however, that a skunk out in the daytime is rabid. It almost certainly isn’t. On the other hand, if it’s displaying abnormal behavior, such as circling, acting aggressively, and having balance issues contact your local animal control department.

* * *

1 The others are the Spotted, Spilogale spp., Hog-nosed, Conepatus spp., and Hooded, Mephitis macroura.

2 Despite their name, stink badgers aren’t badgers; they’re in the skunk family. They inhabit islands of the Malay Archipelago and the Philippine island of Palawan.

3 Merriam-Webster Dictionary

How to remove skunk spray from your pet

Skunks of the U.S.

Proper rescue and care for rescued and orphaned wildlife

Deer frequent questions