Let’s first dispense with the creepy notion that bats are blood-thirsty predators. In actuality, only three species of bats drink blood, and none of them favor human blood. There are about 1,200 species of bats, representing a quarter of the mammals on earth, so the percentage of vampire bats is exceedingly low. Besides, none of the forty-seven species known to inhabit North America are vampire bats, so you can rest easy! Bats are beneficial, nonaggressive, unfortunate victims of myth. These facts about bats will leave you admiring these fascinating, harmless animals. If you have bats patrolling your night skies, count yourself lucky.

Bats are beneficial

Worldwide, about 70 percent of bats are insectivorous, serving as essential predators of crop pests like cucumber beetles and nuisance insects such as mosquitoes and gnats. A single bat can devour hundreds of insects per hour, consuming up to 8,000 in a single night. They employ various feeding strategies, such as scooping insects into their mouths while flying, hunting on the ground or in trees, or using their feet to snatch prey. Bats consume up to half their body weight each night to meet their high-energy needs.

In contrast, fruit bats play a crucial role in seed dispersal and rainforest reforestation. As they consume fruit, they either spit out the seeds or pass them in their feces, aiding in the growth of new trees. Many fruit plants, including bananas, figs, dates, and mangoes, depend on bats for pollination. The ecological impact of fruit bats is significant, with some tree species relying entirely on them for survival.

Additionally, bat guano is a valuable fertilizer due to its nutrient richness. While it can be harvested and sold, excessive collection disrupts the ecosystem by removing food sources for other cave-dwelling creatures and disturbing roosting bats, potentially driving them away permanently.

In the United States, two species of nectar- and pollen-eating bats migrate between the Southwest and Mexico, playing a key role in pollinating plants like the agave, used to produce tequila. The remaining forty-five bat species in the U.S. are insectivorous, distributed across various habitats, and contribute significantly to insect population control. List of U.S. bat species

The Southwest is home to the greatest diversity of U.S. bats, with Texas hosting more than thirty species. Texas’ Bracken Cave, near San Antonio, is home to the largest colony in the world. Twenty million Mexican Free-tailed Bats, Tadarida brasiliensis, swoosh out of the cave at dusk. By dawn, when they return, they’ve feasted on 250 tons of insects! The cave, owned by Bat Conservation International, is closed to the public for the protection of the bats, but you can watch them leaving it.

Background

Fossil evidence points to an ancestor of bats (shared by humans) dating back 80 million years. However, the oldest actual bat species, Icaronycteris index, lived in the early Eocene Epoch, about 52.2 million years ago. Bat fossils show a creature not significantly different from those of today.

Micro and Mega

Bats belong to the order Chiroptera (ky-ROP-ter-uh). There are two major groups within this order: the Microchiroptera and the Megachiroptera.

About 200 species are Megachiropterans, known as Old World or fruit bats. They’re found only in tropical areas of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Some megabats are as small as 2 inches long (5 cm), but this group also includes the large “flying foxes,” which are bats with fox-like faces and large eyes, like the one shown at the top of this page. Some megabats are active in the daytime, but most are either active at dusk and dawn or at night. They eat fruit, nectar, and pollen. Most don’t echolocate. Instead, they use their excellent vision and a good sense of smell.

The rest of the bats, Microchiropterans, inhabit all areas of the world except Polar Regions and extreme deserts. They use echolocation to find prey. Most are insect-eaters, although some species feed on small mammals and fish. All microbats are nocturnal.

The world’s smallest bat (and possibly smallest mammal) is the bumblebee-sized Kitti’s Hog-nosed Bat, Craseonycteris thonglongyai, of Thailand and Myanmar, which is only 1.2–1.3 inches (3.0–3.3 cm) long and weighs just 0.071 of an ounce (2.0 g). At the other extreme is the Giant Golden-crowned Flying Fox, Acerodon jubatus, an inhabitant of the Philippines, which is 7–12 inches (18–30 cm) long, with a wingspan of 5.0–6.0 feet (1.5–1.8 m).

The smallest bat in the U.S. is the Western Pipistrelle, Pipistrellus hesperus, with a wingspan of 7.4–8.5 inches (19–22 mm) and a body length of 2.4–3.1 inches (6–8 cm). The largest U.S. bat is the Western Mastiff Bat, Eumops perotis, 5.5–7.5 inches (14–19 cm) long, with a wingspan of over 22 inches (56 cm).

Myths, be gone!

Bats stay quietly hidden by day and come out at night to silently skim the nighttime sky, which makes them mysterious and seemingly dangerous. But here are the facts:

- Bats aren’t dangerous. To repeat: Bats aren’t dangerous. They couldn’t be more opposite to their fictional counterparts. They’re timid, gentle, and nonaggressive in real life—so much so that even one with rabies won’t attack.

- Bats aren’t “blind as a bat!” Day and night, their vision is excellent. Researchers have discovered that at least two nocturnal bat species have color vision.

- Bats aren’t dirty. They’re very clean, spending about a third of their resting time scouring their entire body, much like a cat does.

- Bats don’t get tangled in people’s hair. Most bats are insectivores, and it’s true they might occasionally get close to us—even very close—while catching flying insects. But they don’t want to touch us and see far too well to do it by accident.

- Rabies among bats makes sensational news, but it’s rare.2 Also, rabies isn’t transmitted through the air, so being near a bat is not a risk.

The nitty-gritty on vampire bats

Vampire bats are Microbats in the family Phyllostomidae, subfamily Phyllostominae. These bats are small, with a body of only about three inches (7.6 cm) long and a wingspan of around eight inches (20 cm).

They do drink blood, as their name says, but they seek it from animals like cattle, pigs, horses, birds, and sometimes other bats. Rarely they’ll bite a human who happens to be snoozing uncovered in the great outdoors, but we aren’t their usual target. Their prey is typically fast asleep when it happens, a cut so tiny with teeth so sharp the victim seldom stirs. The amount of blood loss is so little it doesn’t affect the host, and the bats don’t suck it in, like Count Dracula–they lap it up, about an ounce (30 ml) in thirty to forty minutes.

Don’t worry yourself with mental images of a vampire bat attacking your big toe if it escapes from under covers while you’re camping—that is, unless you plan to do it where they live, Mexico and Central and South America.

Vampire bats are intelligent and can be tamed and trained—NationalGeographic.com reports a researcher with vampire bats that come when called by their name. Bats are also charitable: females have been observed feeding new mothers for two weeks after they give birth.

Physical characteristics

Bats aren’t birds. They’re mammals, the only ones that truly fly rather than glide from a higher elevation to a lower one, such as “flying” squirrels do.

Bats tend to have black or brown hair, but there’s some diversity in size, facial features, and hair color. For example, the Northern Yellow Bat, Lasiurus intermedius, is often yellowish; the Silver-haired Bat, Lasionycteris noctivagans, has dark hair tipped with silver, giving it a frosted look; and Eastern Red Bats, Lasiurus borealis, have a reddish-orange coat. Some bats have elongated snouts suitable for sipping nectar in flowers, and some have pig-like noses or intricate facial folds. Here’s a sampling of some of the many different features and colorations.

You’ll notice that some of the bats shown above have a strange flap of skin around their nostrils. They’re among those that emit sounds through their nose. The skin is called a nose leaf, and it’s believed to help them focus their echolocation.

Bats have excellent hearing; many can rotate their ears to gather sound even better. Ear size and shape vary from small and round to large and pointy. Their calls are extremely loud, so much so that small muscles in their middle ears contract to dampen the vibrations of their own echolocations. This temporary reduction in hearing sensitivity helps protect their inner ear from damage. The timing between emitting a call and listening for its echo is finely tuned. Bats can rapidly switch between calling and listening, minimizing the overlap between the outgoing sound and the incoming echo.

Wings

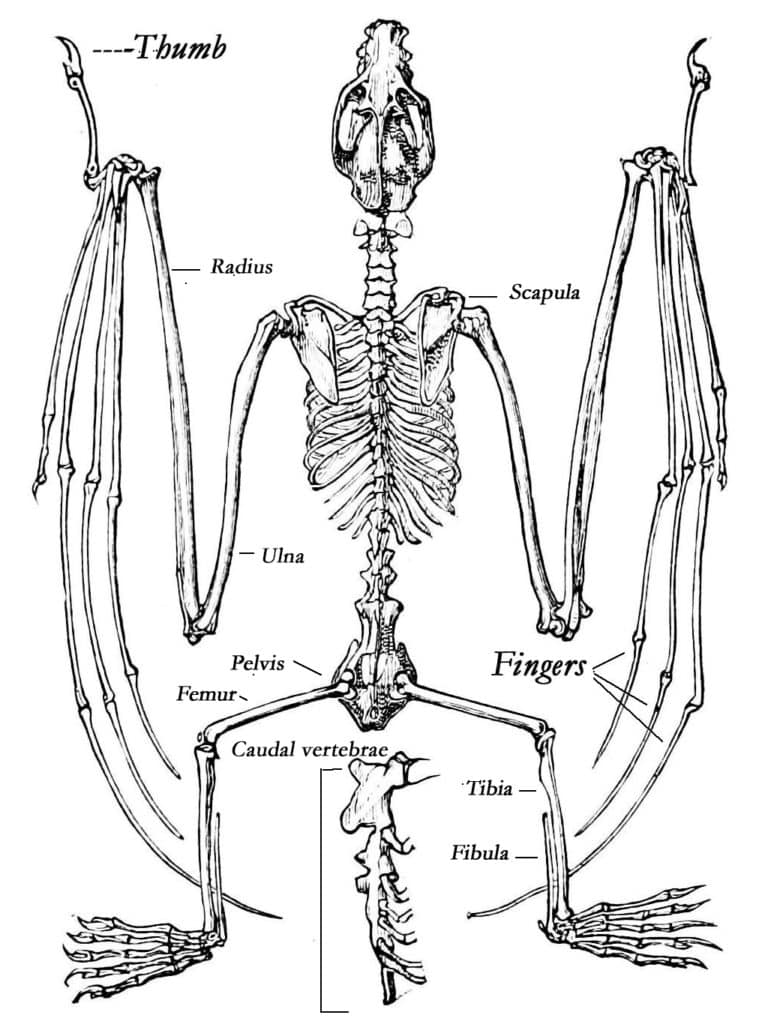

“Chiroptera,” the name of bats’ order, is a word from the Greek cheir, meaning hand, and pteron for wing. Hand-wing. It’s well-chosen because their wings have elongated bony structures that work like the fingers of a hand. They also have a thumb on each wing tipped with a claw they use for holding food, climbing, and clinging.

Common Pipistrelle, Pipistrellus pipistrellus. Its thumb is the pointy projection on the folded wing. (Gille San Martin / Wiki; cc by-sa 2.0

A bat’s wings are covered by the patagium (puh-TAY-gee-um), a membrane of skin so thin that light can be seen through it. It gives the appearance of being hairless, but with at least some species it’s coated with tiny, inconspicuous hairs thought to play a role in aerodynamics or as sensors.

Mexican Long-tongued Bat, Choeronycteris mexicana. Note how the bones of the arms, finger, legs can be easily seen through the thin patagium. (Ken Bosma / Wiki; CC BY 2.0)

The patagium extends from the tips of the fingers back along the arm bones to the shoulder and then all the way down the body to the ankle. This membrane also stretches between the legs, where it’s then called the uropatagium or interfemoral membrane.

Legs

Bats’ legs are oriented differently from those of other animals. Very differently: Their knees bend backward, enabling them to comfortably hang against a surface, usually head down, without their knees getting in the way.

Bats hang by their five toes using a system of tendons that clench when the body’s weight pulls against them. That allows bats to sleep without losing their grip. Because of that, if a bat dies while roosting, its body will hang there until something knocks it loose. (Bird feet also have tendons that hold them in place, but in their case, in an upright position.)

Flight

Bat wings move with all the flexibility of hands (and then some), giving them astonishing maneuverability in flight. For instance, they can turn 180 degrees in less than half the span of their wings and perform aerobatics that would crash a bird into the ground. Bats have speed, too, able to easily fly at 35–40 miles per hour (56–64 kmh). In at least one instance, even faster: In 2016, University of Tennessee researchers clocked a Mexican Free-tailed Bat, Tadarida brasiliensis, at one hundred miles per hour (161 kmh),1 a new record for horizontal flight among bats, birds, and all other animals, making it the fastest animal in the world.

The upside to upside-down

You’ve seen photos of bats, and they always appear to be hanging upside-down. There’s an anatomical reason for that. It’s because their wings don’t produce enough lift for takeoff from a standstill, and they can’t run fast enough to lift themselves into the air. So, bats simply let go from an elevated position and fall headfirst into flight. If you were to place a bat on the ground, it would walk to the nearest vertical structure and climb it to gain some height before taking wing. Now, that said, it may surprise you that bats don’t always face head-down when they rest.

Bat-speak

Bats use vocalizations to communicate with other bats. And they’re surprisingly complex, at least with Mexican Free-tailed Bats. Dr. George Pollak, a physiologist at the University of Texas in Austin, has been studying the vocalizations of a captive colony of these bats. He describes their vocalizations as made up of syllables and phrases, with “what seems to be some kind of syntax.” He says they’re also “situation-specific.” This complexity probably extends to other bat species, as well. Pollak attributes this to bats’ need to communicate in the dark, where they can’t transmit physical clues.2

Echolocation

Most people believe bats can fly in the dark without smacking into things because they use “radar,” or electromagnetic radio waves. That’s the right idea, but not entirely accurate. What they use is sonar which is a sound wave. There’s a specific term for sonar when used in reference to animals—echolocation.

Cover your ears!

A bat emits constant high-frequency, short-wavelength sounds while flying. They’re produced in the larynx and emitted through the mouth (usually) or the nose. The sounds, or calls, are often described as clicks or cheeps, and they can be very loud—up to 120 decibels, louder than a low-flying jet plane. (Fortunately for humans, most ultrasonic sounds are beyond our hearing range.) As the sound waves strike objects in their path, they bounce echoes back to the listening bat, which can interpret them to form a mental picture of what’s ahead. It’s comparable to someone who shouts in a canyon: the sound waves travel, hit the walls, and bounce back, creating an echo. However, a human’s perception isn’t very precise, while the image is so well-formed for a bat that it can “see” a single hair or home-in on a mosquito on a moonless night.

The volume, frequency, tone, and duration of calls vary depending on the bat’s surroundings. Most are high-frequency sounds we don’t hear, but sometimes calls are made within our hearing. The Western Mastiff Bat regularly calls in a lower range. Listen to a Western Mastiff Bat calling.

Not all bats use echolocation. In a bit of evolutionary logic, bats that don’t use it have larger eyes and better vision than those that do. (Bats, by the way, aren’t the only species that use echolocation. Whales, dolphins, porpoises, and some species of shrews are some of the other animals that do. And some blind people use it very successfully in their daily lives, making “clicking” sounds, just as bats do, although at a lower, slower frequency.)

Roosting

The human vampires in literature and movies would have us believe bats burst into flames if caught in sunlight! Of course, bats don’t actually do that, although they’re nocturnal (except for some tropical bats that eat in the daytime). When not feeding, bats “roost,” meaning they find a safe place to groom and rest.

Roosts may be in caves, abandoned buildings or mines, rock crevices, under bridges, in attics, under louvers or siding, and in other places where they cling to vertical surfaces. Any sliver of an opening is all they need for entry. You may discover a bat roosting under loose bark, within a hollow tree, clinging to its trunk, or just hanging from a limb. Where you won’t find them is on any surface that prevents them from falling downward to take flight.

Seba’s Short-tailed Bats, Carollia perspicillata, roosting in an old building (Bernard Dupont / Wiki; CC BY-SA 2.0)

Some bat species are solitary, but most are highly social and roost in colonies of a few up to millions. Indiana Bats, for example, sometimes cluster so tightly that 500 of them can fit within a square foot (0.09 sq m)! Males and females of some species stay separated except during mating season. Other species roost together, except in summer when females form maternal, or nursery, colonies.

Reproduction

Sexual maturity begins anywhere from eight or nine months old up to two or three years, depending on the species. It usually occurs once or twice a year, and the gestation period ranges from about six weeks to six months or more with some of the fruit bats.

Bats don’t construct nests, even when pregnant. Pregnant females roost together in maternal colonies, which are sometimes enormous. At the birthing time, the mother may separate from the group. Often, she turns her body upward and forms a pouch with her interfemoral membrane (uropatagium). She uses it to catch her baby when it emerges.

Lesser Short-nosed Fruit Bat, Cynopterus brachyotis, less than 12 hours old (Anton Croos / Wiki; CC BY-SA 4.0)

The “pup”—usually one, occasionally two, rarely four—is born feet first. It’s bald, sightless, and a quarter or more the size of its mother. She licks it clean, head to toe. The pup is strong, a good thing because it must climb up its mother’s body to suckle. It’s a perilous journey for the tiny baby—if it loses its hold, the fall could kill it. If it survives a fall, it’ll call out loudly. The mother has a strong maternal instinct and will do her best to rescue her pup. She’s protective, too. She’ll move with her baby to a different location if her roost site is disturbed.

Some species carry their pup with them for the first few days while foraging, the baby clinging tightly to its mother’s underside. But as pups put on weight and become too heavy, they’re left in the roost. You may wonder how the mother can pick her baby out of dozens, hundreds, even thousands of other pups packed tightly together. She identifies it through odor and vocal communication. Listen to a young fruit bat calling for attention.

Within a week of birth, the pup opens its eyes. In a couple more, it has fur. It starts flying in three to six weeks, and it’s fully weaned a few months after that.

Lifespan

Bats can live twenty to thirty years, but their mortality rate is very high in their first year. This is due to predation, accidents, failure to put on enough fat to last through hibernation, and forced abandonment of young caused by human harassment. All this, combined with bats’ low birth rate, means it takes a very long time for a partially destroyed colony to rebuild itself, if ever.

Food sources

Depending on the species, bats eat beetles, moths, mosquitoes, and other insects, as well as nectar and fruit. A few species are carnivorous, feeding on frogs, lizards, birds, small mammals, and fish, generally killing them very quickly. Vampire bats feed only on blood.

Habitat

Nectar-eating bats and insectivorous bats inhabit distinct habitats that reflect their dietary preferences and foraging behaviors. Nectar-eating bats are typically found in tropical and subtropical regions with abundant flowering plants. They often inhabit rainforests, woodlands, and areas with dense vegetation that support a high diversity of flowering plants. The U.S. has two species that eat nectar and pollen. They both inhabit the Southwest.

In contrast, insectivorous bats have a broader range of habitats, reflecting the wide distribution of their prey. These bats can be found in various environments, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands, deserts, and even urban areas. Their adaptability to different habitats is enhanced by their ability to exploit multiple insect populations. Some insectivorous bats are even found in high-altitude regions and cooler climates where insect activity is seasonally abundant.

Water sources, such as rivers, lakes, ponds, and artificial water features like fountains and swimming pools, are particularly attractive to bats in urban areas. These water bodies attract insects and provide hydration. Bats are frequently found near urban water bodies, where they can efficiently hunt for insects.

While water sources are important, bats in urban environments are quite adaptable and can be found in a variety of settings. They may roost and forage in residential neighborhoods, industrial areas, green spaces, and along tree-lined streets. Urban gardens, parks, and green belts offer additional foraging opportunities, especially for bats that rely on flowering plants and fruit trees.

Hibernation

Most bats are insect eaters, so those living in colder climates hibernate the six or so months of the year when insects aren’t readily available. Their winter quarters (hibernaculum) must be frigid enough to lower their body temperature considerably, but not to the freezing point.

When hibernating, they allow their temperature to drop to match that of their environment, dramatically reducing their energy requirements. Their resting heart rate slides from two or three hundred beats per minute down to ten or twelve. Breathing slows to perhaps one breath every forty-five minutes. They hang by their toes, which also saves energy because it doesn’t require using muscles.

Before hibernating, bats fatten up to have enough “fuel” to carry them through to spring. They awaken periodically through the winter to urinate or change position. Each awakening consumes enormous amounts of energy. So, it comes at a high cost when their hibernaculum is disturbed: the consequence is death if one runs out of stored fat before insects are available.

And that can easily happen. For example, a study showed that each time a Little Brown Bat, Myotis lucifugus, wakes from hibernation, it expends sixty-seven days’ worth of fat. Where we humans can become fully alert in seconds, or a few minutes, a bat coming out of hibernation must ignite its internal furnace, slowly raise its temperature, increase its heartbeat, and draw more frequent breaths. It’s a long process.

Predators

Numerous animals prey on bats. Raccoons, snakes, weasels, and others crawl or reach into places where bats are roosting in the daytime. Fish catch them as they’re skimming above water. Hawks and owls snatch them out of the air when they leave or go to their roosting places at dawn and dusk. Large spiders, such as tarantulas, also occasionally catch bats. Encroachment, harassment, deliberate killing, habitat destruction, and wind farms threaten more than 50 percent of U.S. bats.

Bats and rabies

“Rabies” (a singular noun, even though there’s an ‘s’ at the end) is carried in saliva and transmitted through biting, which bats don’t do unless forced to. Not even if they’re rabid. It isn’t true that one seen out in the daytime must be rabid. Some species rest in crevices, under eaves, or even hanging from tree limbs, where they might be seen.

Rabies among bats is rare. Only 1,241 bats nationwide were diagnosed with rabies in 20213 (the most recent report from the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association). Some states had no cases at all. Any case of rabies, of course, is one too many, but to put that figure into perspective, consider that there are millions of bats across the country. Of course, never touch one unless it needs help. And, even then, never bare-handed.

| 1 Matthew L. Miller, “Bet You Can’t Name the World’s Fastest Mammal,” Nature.org, October 10, 2018, https://bit.ly/3Ng0Bet |

| 2 Locke, Robert, “Bat Talk: Do Bats Use Language,” Batcon.org, Vol. 22, No. 3, Fall, 2004, https://bit.ly/3VrJtrF |

| 3 2021 Rabies Surveillance Report, state by state |