Ants can lift 9,000 pounds over their head and run 52 miles per hour (84 kmh) relative to their body size! There’s even one species—the Florence Griffith-Joyner of the ant world—that can run at the human equivalent of 400 miles per hour (644 kmh)! Ants, almost all of them females, are physically amazing, but did you know there’s more to them than just vigor and brawn? They manage “cities” and “farms” and have the largest brain-to-body weight of all animals. You’ll uncover many more interesting facts as you learn all about ants.

Jump down to: Beneficial, Background • Physical description • Head, Brain, Mouth, Antennae • Senses, Pheromones, Communication • Thorax, Appendages • Abdomen, Heart, Organs, Breathing • Eusocial, Castes • Reproduction, Eggs, Larvae • Nests, Anthills, Bivouacs, Sleep • Foods, Predators, Defenses, Lifespan

Ants are beneficial

You’ve probably noticed the whirl of activity that always surrounds ants, but what are they accomplishing other than stealing our tasty picnic foods? Well, quite a lot, really—they’re among Earth’s beneficial wildlife, and here’s why:

- Some ants prey on other insects and their eggs, which helps to control pest populations.

- Their tunneling in soil aerates it, allowing water and nutrients to penetrate down to plant roots. “Tunneling ants turn over as much soil as earthworms do,” according to FineGardening.com.

- They disburse seeds.

- Ants protect nectar-producing plants from herbivorous insects.

- Ants themselves are food for other beneficial wildlife.

Background

Ants have a long history. Fossil evidence shows they evolved from a lineage of stinging wasps and have existed for at least 92 million years, since the Cretaceous Period. Their longevity is thought to be related to a high level of social organization, which helped them adapt to environmental changes throughout the ages.

Respected sources vary as to the number of ant species in the world. It’s anywhere from 8,800 to 12,500,1 but all agree there are many more awaiting discovery. Ants are found nearly everywhere except for Antarctica and a few islands. In North America, there are about 1,000 species. Ants of N.A.

Ants are called “eusocial” insects, which means they live in highly organized colonies that vary in size from dozens to millions of individuals. A supercolony found in Japan had an estimated 306 million workers and one million queens living in 45,000 interconnected underground nests! Overall it covered 670 acres (271 ha).

The word “ant” derives from the Old English æmette and the German word Ameise, plus a compound of other word forms. It means “the biter off,” perhaps a reference to their biting habits. They belong to the taxonomic order Hymenoptera (hymen-AWP-ter-uh), along with bees, wasps, and sawflies. Ants, wasps, and sawflies (but not bees) are further classified into the family Formicidae (form-uh-CID-ee).2

Physical description of ants

Ants are invertebrate animals (yes, they’re “animals,” as they fit all the definitions of that). They have a hard, protective skeleton made of chitin, the same material that forms our fingernails. Unlike humans, however, it’s on the outside of the body and called an exoskeleton.

Our U.S. yards teem with ants, some so small they’re nearly invisible, others alarmingly large. Those in the genus Carebara, a species found around the world, are only 0.030 inches (0.76 mm) long, while the Black Carpenter Ant, Camponotus pennsylvanicus, probably the largest in N.A., measures about 0.5 inches (1.25 cm) long. That seems large, but there are eight South American giants in the genus Dinoponera that measure 1.2 to 1.6 inches (3–4 cm)!

Most ants don’t have flashy colors, all the better to stay camouflaged in their environment. They’re primarily various shades of reddish-brown, brown, or black. One exception in the U.S. is the reddish color of fire ants, genus Solenopsis. (You may have seen “Velvet Ants,” which are bright red, but they’re actually wasps.) There are also a few species of ants in Australia and South America that are green, gold, or greenish-blue.

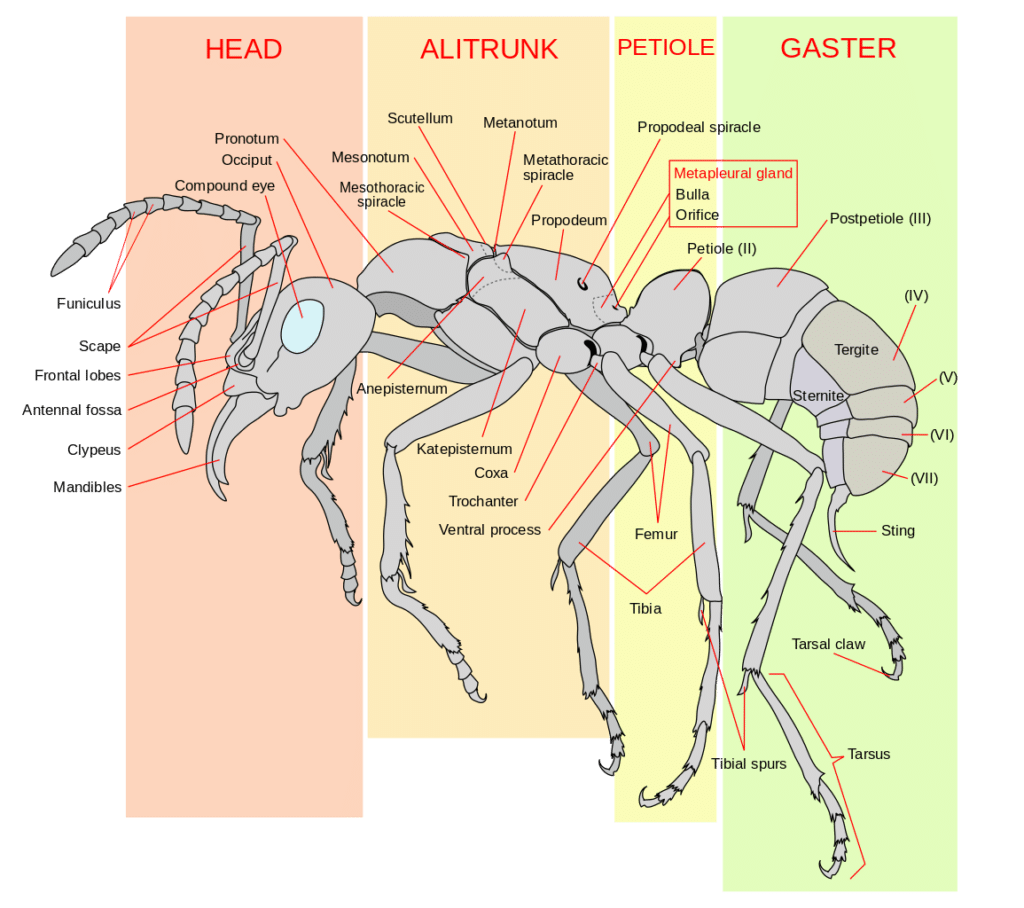

Three main body sections—head, thorax, and abdomen

Head

The ant has two large, dark, compound eyes and three simple eyes called ocelli (oh-CELL-ee), grouped as a triangle near the back of the head. The compound eyes detect movement, while ocelli discern light and polarization. Two moveable antennae with elbows are attached to the front of the head; they’re used for smell, touch, feel, and to communicate with other ants.

Brain

Entomologists have long accepted that the collective intelligence of an entire colony is what imparts intelligence to each of its members; in other words, an ant without a colony is clueless. An ant brain is mainly a bundle of nerves and fibers. It consists of only about 250,000 cells (for comparison, humans have about 100 billion).

Senses and communication

Ants have five senses: touch, smell, taste, hearing, and vision.

Touch: Look closely, and you’ll notice how frequently ants use their antennae to touch each other. They’re exchanging information about who they are, the colony they belong to, and where they’ve been.

Pheromones and smell: There are pheromone glands throughout the ant’s body, and they’re very specific. For instance, these chemical signals can mark a trail for others to follow to a good food source. An injured or crushed ant will emit a pheromone that triggers alarm. Pheromones are also secreted to mark territories, mark the way to new nest sites, and trigger sexual behavior. A single trail may consist of several different pheromones from one or more glands.

Recent research has shown that trail pheromones are remarkably sophisticated. They provide information about previously used trails, current trails, and unrewarding branches. There are workers who are specialized in laying trails and detecting them.

Antennae are super-sensitive

The antennae play an essential role in the sense of smell. They contain four to five times the number of odor receptors of most insects and are used to detect food. Research shows these receptors are so keen they can distinguish between two molecules that differ only slightly.

Taste: An ant’s sense of taste is closely linked to its sense of smell. They don’t have actual taste buds, but taste receptors located in the mouth and the chemical odor receptors in the antennae combine to give them a sense of what something “tastes” like.

Hearing: Ants don’t have ears, but they can “hear” by feeling and interpreting vibrations through different body parts, such as their legs and antennae.³

Extreme close-up of an ant, showing the numerous ommatidia of its compound eyes (Retro Lenses / Wiki; CC BY 4.0)

Vision: This is the least important sense, even though ants have five eyes. Two are their compound eyes, which are comprised of many singular units. Each unit, called an ommatidium, has its own tiny field of view, and the nervous system combines all to produce a complete picture. However, it’s a blurry one. There are also three simple eyes, each with a single lens that’s fixed and doesn’t adjust for close-up and distance. Their purpose is to monitor light intensity. Ants see well enough to navigate even the most challenging terrain, although a few subterranean species are blind.)

Thorax

The thorax is the middle section of an ant’s body. Six strong, jointed legs, three on each side, are attached to it. At the end of each leg are two hooked claws and a dense array of fine hairs, which are used for gripping surfaces and other ants.

On their feet are pads that can stick to vertical surfaces. How? The secret is that the pads are wet and create a strong surface tension between a foot and the surface it’s on. The ant un-sticks by folding its foot up. (A good comparison is when surface tension causes a wet glass to stick to a coaster, but tilt it slightly, and it releases its hold.) Asian Weaver Ants (genus Oecophylla) create such strong surface tension they can walk across glass upside down while carrying up to one hundred times their body weight! Video of Asian Weaver Ants and how they do it

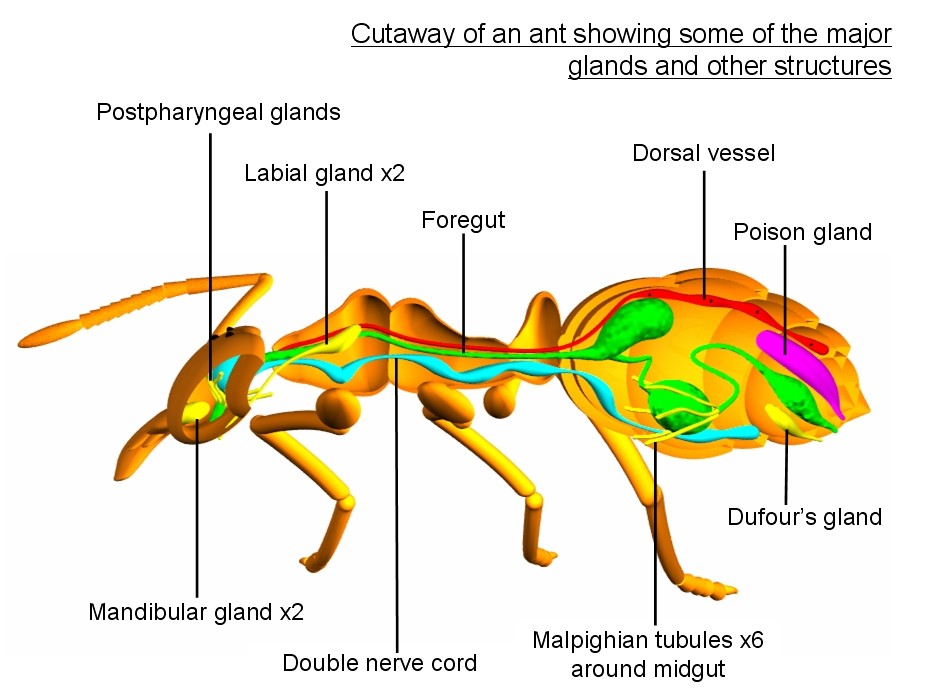

Extending into the thorax from the head are the esophagus, labial glands (which aid in digestion), and nerve ganglia (which supply commands to the legs and wings and interpret sensory input from the eyes). Between the thorax and abdomen is a node that looks like a waist. Called a petiole, it’s another digestive aid and has either one or two segments, depending on the species. (This physical feature helps taxonomists identify ant subfamilies.)

Abdomen

The ant’s largest body section is the abdomen. It contains nerves, vital organs, including the “heart,” part of the digestive system, and reproductive organs.

Heart: Ants don’t have a heart as we know it. Instead, the dorsal aorta, a pump of sorts, takes its place. Its job is to move blood to the ant’s head. From there, blood washes backward through the rest of the body. There are no vessels involved—it floods around the organs in what’s called an open system.

Reproductive organs: Queens and worker ants (who are always females) have egg-laying tubes called ovipositors, but typically only the queen lays eggs. The workers of many species, but not all, have modified ovipositors through which a toxin from the “poison gland” can be injected. The toxin in most species is formic acid,2 a strong and irritating chemical—this is what gives fire ants and others their painful “fire.” Also, in the abdomen is the Dufour’s gland, which secretes a pheromone used as a trail for other ants to follow.

Respiration: Ants don’t have lungs to pump air in and out. Instead, through a process called rhythmic tracheal compression, they breathe passively through a series of tiny pores located on their body. Called spiracles, they attach to tube-shaped trachea that grow narrower and narrower as they network through the body. As the ant moves, it draws air in and out.

Learn more about insect anatomy

Eusocial living

Ants, along with various bees, wasps, and termites, are called “eusocial” because they live in a cooperative group that organizes work efficiently by dividing tasks and sharing information. This behavior seems to give them an advantage over solitary insects. For example, by sharing, ants can convey to each other the shortest distance between two routes to get to a good food source.

It’s commonly thought that ant colonies have only one queen, but depending on the species, there may be more. Or none: Some colonies, called gamergate colonies, have no queens, and all the workers there, called gamergates, are females capable of reproducing. Usually, only a few among them do, however. In colonies that have more than one queen, they tolerate each other, and sometimes one might leave with a band of workers to form a new colony.

Castes in an ant colony

Big-headed Ants, Pheidole californica, showing queen, soldier, worker, and larvae (Alex Wild / Wiki; PD)

Typical ant colonies have at least three kinds of ants—a fertile queen, fertile males, and non-reproductive females called workers, but some species have additional castes of workers.

- Queens spend their entire lives laying eggs; it’s their only role.

- Males have only one job, to mate with the queen.

- Workers do everything else in a colony and are assigned specialized jobs. The smallest ants, called minor workers, find and gather food; clean, maintain and expand the nest; feed and care for the queen; and care for eggs and larvae.

- Major workers, sometimes called soldier ants, are larger and stronger than other workers. They have a large head with powerful jaws designed for specialized tasks, such as seed-cracking, wood-boring, or combat.

- Median workers fit, in size, between major and minor workers and also perform tasks to support the colony.2

Reproduction

An ant’s life cycle involves a process called complete metamorphosis, which means it progresses from an egg to a larva to a pupa to an adult.

It all begins in late spring to early summer when winged virgin queens and males simultaneously leave their existing colonies in vast swarms called “nuptial flights.” They go far away, where they’ll mate (in the air) with ants from different colonies to prevent inbreeding. Males die soon after mating, having completed their role in life.

After mating with one or more males, the queen flies off to find a suitable nesting site. There, she drops her wings to the ground, never to be used again. Her task now is to construct a nest.

A young, fertilized meat ant queen, Iridomyrmex sp., excavating a hole for her nest (Fir0002:Flagstaffotos / Wiki; GFDL 1.23)

Nest-building, raising first offspring

Depending on the species, it might be in the ground, wood, walls, cracks in the pavement, or nearly anywhere suitable for a long tunnel with a small chamber at the end. She usually excavates it alone, then seals herself in the nest and lays eggs. Alternatively, queens sometimes wait until the following spring. Either way, she’ll raise her first group of workers alone and stay in total darkness for the rest of her life unless her nest is damaged. (Queens of some species cooperate and raise the first brood together. If this occurs in a species that’s ultimately to have only one queen in a colony, called monogyny, the once-cooperative queens will fight to the death of one of them.)

Eggs, larvae

The young queen feeds salivary secretions from her mouth to her first brood. She doesn’t eat during this time. After her first workers are grown, they take over the care and protection of all following eggs and larvae.

An ant egg is extremely small, about 0.02 inches (0.5 mm) in diameter, and weighs only 0.0005 grams (0.000017636981 ounces)! It’s kidney-shaped and sticky, which bonds it to other eggs. This allows adults to carry many stuck-together eggs at once, which is important in an emergency.

A larva hatches in five to seven days and looks like a tiny maggot. It doesn’t have legs, but it can move minimally. At first, it’s fed juices made from soft, regurgitated food and, later on, solid foods. It sheds its skin (molts) each time it outgrows it. It also gets hairier. Some of the hairs are hooked at the end and can lock to other larvae—this allows workers to carry several at a time when necessary. At the last molt, larvae are too large to be carried as a group.

Haplodiploidy

The queen has the ability to control the sex of her offspring through a process known as haplodiploidy. She can lay unfertilized eggs that develop into males or fertilized eggs that become females. Additionally, she can store fertilized eggs in her spermathecae, or “sperm pocket,” for future use. The queen possesses enough sperm to last her lifetime, allowing her to fertilize millions of eggs. When she stops producing a particular pheromone, it signals the workers it’s time to start raising new queens.

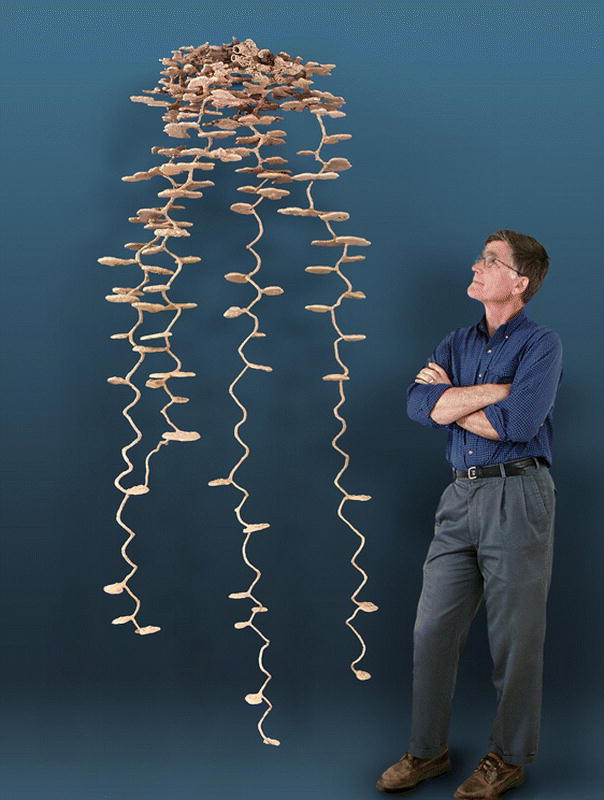

Ant nests

An ant nest is where a colony lives, its “city,” so to speak. It may be underground, in wood, under stones, in mulch or debris, in walls, or in mounds of soil. Gardeners find them under or in flowerpots or even within an unused water hose.

Nests are highly structured, with a network of chambers connected to each other by tunnels. Some chambers are nurseries, others are used for food storage. Ants in a German study in 2015 had some set aside for “bathrooms.”

Nests begin small and expand as a colony grows bigger. Corridors and chambers may interconnect for vast distances. In 2004, one in Australia measured 62 miles (100 km) wide, most of it underground. Some nests may trail down 26 feet (2.7 m).

Anthills

An anthill is formed from the excavated soil and debris that ants carry from belowground as they dig tunnels and chambers. Generally, it’s deposited in a circular pattern around the entrance hole. You’ve probably seen these “volcanos” in your own yard.

Watch an abandoned ant hill excavation and the amazing results.

Ant bivouacs

You may have heard of ant “bivouacs.” These are temporary camps made up of army ants (over 200 species in several genera), who defy custom by not building permanent nests. An entire colony travels nearly continuously in search of food. When the ants come to a halt, they link their bodies together until they’re ready to travel again.

Sleep

Ants need some rest, especially considering their hectic pace of activity. So, they take some time off, however brief. A 2009 University of Florida study of fire ants showed that each worker took an average of 250 one-minute naps a day. Nap times were staggered, so some workers were always awake while others slept. Queens took about ninety six-minute naps a day—and studies of their brain activity suggest they have dreams.

Foods and farms

Ants are opportunistic omnivores. Because they’re scavengers, rather than hunters, they eat what they come across. Generally, they feed on soft-bodied animals, such as mites and spiders, the larvae of other insects, and carrion. Species in some parts of the world eat seeds or fungi. Ants also eat sweets—candy, honey, fruit, and jam—which provide carbohydrates for energy.

Many ant species maintain herds of aphids because they like a sweet solution secreted by them called honeydew. In return, the ants protect their “livestock” from predators and even keep them corralled! Look closely if you see a group of aphids on your plants, and you may spot some ants tending to them.

Predators

Predators of ants are birds, lizards, some species of spiders, other insects, including other ants, armadillos, anteaters, and Aardvarks.

Defenses

Ants have several defenses. They can bite (many are too small to inflict a wound on human skin). Most can sting. Reportedly, the sting of the Bullet Ant, Paraponera clavata, a large Rainforest species, is worse than any other ant, wasp, or bee—according to some human victims, its sting is equivalent to being shot (hence its name). A few species are capable of spraying formic acid onto the skin and eyes of predators, leaving them in pain and temporarily or permanently blind. Ants may use other tactics, too, such as blocking the entrance to their nest with their heads (a behavior called phragmosis) to prevent enemies from entering. The Fish-hook Ant, Polyrhachis bihamata, another Rainforest species, has sharp spikes on its back, which can be used to interlock with other ants to prevent one of their own from being dragged away. They also use them to stab enemies.

Lifespan

Queen ants may live up to thirty years, the longest span of any known insect. Workers live one to three years (up to four in a lab). Male ants die soon after mating.

| 1 National Geographic says “more than” 10,000. Animal Diversity says 8,800, Britannica.com says “approximately” 10,000, and Wikimedia reports “more than” 12,500. |

| 2 “Formic” comes from the Latin word for ant, formica. Formic acid, which was originally distilled from ant bodies, is now produced through chemical compounding. It’s primarily used by industry as a preservative and antibacterial agent. |

| 3 GDFL License Documentation |

| 4 Ant bathrooms |

More reading

About specific ant species

More about eusocial insects and communication

A fun and interesting read: 7 Reasons Ants Will Inherit the Earth

Learn also about spiders and termites

Spider magic: silk, spinnerets, webs, and spiderlings

All about termites