A thriving backyard wildlife habitat provides four essentials that are basically the same ones humans need—food, water, shelter, and safe places to raise their young. Creating such an environment is all about planning and planting, and it needn’t be complicated. If designing a habitat is a bit more than you want to take on, consider hiring a landscape designer. Most people, though, try it themselves with satisfying results.

Start small so you won’t get overwhelmed. Begin in one or two areas and each year expand a bit. As your plantings grow, so will the variety and number of wildlife that come to visit. If you wanted to, you could throw all their needs together in a wild unplanned jumble, but you will probably enjoy it more if it’s visually appealing to you, too. Here’s how to set that in motion.

Draw

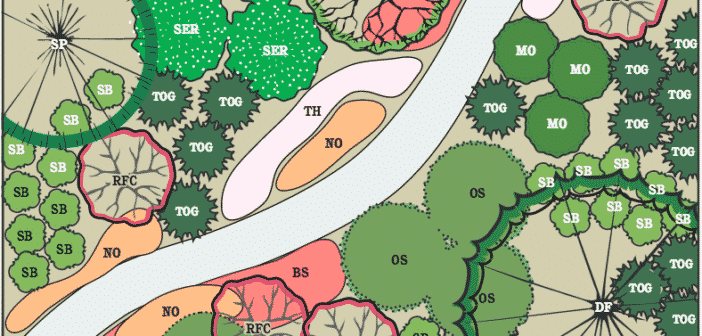

Begin by drawing the dimensions of your yard (or the area you’re converting to wildlife use). Use graph paper so you’ll be designing to scale.

- Add all permanent structures, including your house, shed, patio, pool, deck, utility boxes, easements, and anything else that won’t change.

- Add the location of all existing plants, trees, pathways, and play areas you intend to leave unchanged.

- Note any structures or views you want to hide (such as a neighbor’s old shed).

- Sketch where you want to add trees, flowerbeds, water features, birdbaths, and yard ornaments. Space plants according to their mature size. Also, consider the shade that will be cast by plants and shrubs, your house and other structures, and trees as they age.

You might want to use colors on your plan because they provide a better visual interpretation of the layout than black and white. For example, use a blue marker to color areas where water stands after it rains; that could become a bog area for water-loving plants. Brown could represent a rocky or sandy area suitable for sedum, salvia, and other low-water plants. Gray might be used to indicate the shade thrown by trees and structures. Consider, too, that shade might be heavier on one side of a plant than another, depending on its location in your yard relative to the sun.

An enhancement to the above is to draw a black-and-white master copy and use a series of transparencies to lay over it. On one, you might show all upper-story trees. On another, understory trees and shrubs that tolerate shade. One might indicate the location of birdhouses, bird feeders, and birdbaths. Use any number of transparencies—laid one atop another, they present a complete picture of your yard. You can quickly alter them by using erasable markers. A clipboard is an excellent way to hold them in place.

Assess

Consider each existing plant and tree in your yard, asking yourself:

- Does it provide at least one of the four basics? If not, are you willing to part with it?

- Is it located in a suitable spot within your planned habitat? If not, can it be moved?

Be especially thoughtful about removing trees, particularly mature ones. First, there’s the cost. But, also, any tree provides at least some benefit to wildlife. Depending on their placement, they also provide shade for your yard and possibly your house. And, they add “curb appeal” and visual beauty that you may later regret giving up—mature trees usually add value to a property.

Before removing a tree to gain more sunlight, consider whether thinning the branches would suffice. If it doesn’t pose a danger, leave dead trees standing—cavity-nesting birds will appreciate them.

Reduce turf

Set a goal to reduce your lawn area to 40 percent or less.1 Consider replacing water-greedy fescue, bluegrass, or other cool-season grasses, with buffalograss, which requires little to no care once established.

Define edges

Edges are the areas where two different habitats meet, such as the border between a wooded and a grassy area, and they support the greatest number of wildlife species. To keep areas you intend to naturalize from looking unplanned or haphazard, define them with pathways, edging, irregularly placed boulders, fencing, or by placing formal plants in the foreground.

Paths help define borders. A backdrop, such as a fence, makes plants stand out. (Patrick Standish / Flickr cc by 2.0)

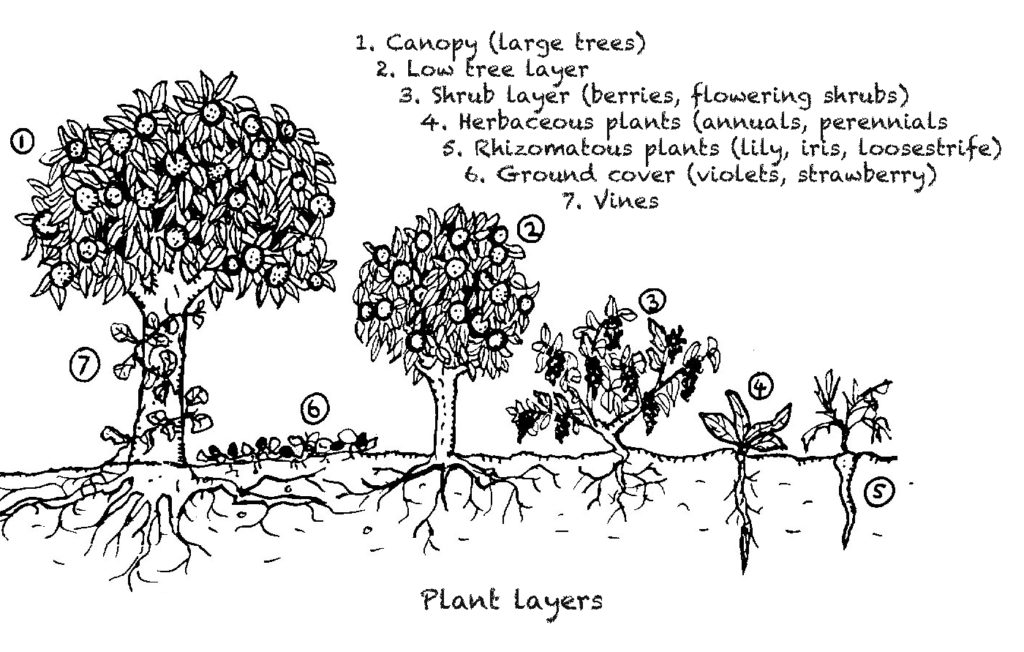

Add layers

In nature, plants grow in layers. Tall trees form the canopy. Beneath them grow smaller trees and tall shrubs. The bottom layers are made up of shorter shrubs and shade-tolerant plants. Creating layers is important because different species prefer different layers. For example, many birds like to perch at the top of tall trees, but American Goldfinches and hummingbirds like shrubby layers.

Plan for year-round cover, food

Provide cover year-round by including plants that stay green, such as conifers and junipers. Well-chosen deciduous trees and shrubs lose their leaves in the fall, but their berries and nuts will provide food into winter.

Design with style

Don’t overcrowd planting areas. The smaller the size of the garden, the fewer the number of species you should use. That will keep it from looking messy.

- Appeal to butterflies and birds (and humans, too) by planting flowers in drifts of a single type of plant to add bursts of color and soften edges between species.

- When deciding where to position new plants, arrange and rearrange them to your satisfaction before removing them from their pots.

- Unify. Let beds flow into one another.

- If possible, use quart-size or larger plants so your planting area will have a more mature look right from the start (and the plants will have a better chance of survival, too).

Add enhancements

These features will make your yard even more inviting to wildlife:

- Stands of tall, native grasses

- Brush and rock piles

- A small pond or water feature

- Bird feeders

- Birdbaths

- Birdhouses

Think outside the box

Don’t have enough space in your backyard for everything you want to do? Consider re-purposing your front yard from grass and shrubs into a wildlife habitat.

Do you live in an apartment? Create a wildlife habitat on your deck or porch using flowerpots, whiskey half-barrels, hanging planters, a railing-mounted birdbath, and a bird feeder. Apply the tips listed above, but on a tiny scale.

Prepare before planting

Before planting anything, remove all unwanted elements, such as debris and unused structures. If you will be doing deep digging, have your utility lines marked beforehand. Bury water and electric lines leading to a pond or water feature.

Do your work in progressive steps: Subdivide the project by taking a section of a bed or a small part of your yard and complete that before moving on. Start at the back of the area and work forward. First, add hard features, like boulders, fences, and walls. Then pathways. Ready the bed by pulling weeds and adding soil amendments, if needed. Now, it’s time to plant your trees and shrubs. Finally, top off your hard work with birdbaths, feeders, benches, and yard ornaments.

Go native

It isn’t strictly necessary to use native plants, but there are significant benefits. Native plants have evolved over thousands of years to be at home in your soil, your climate, and with the wildlife of your area. They’ll be hardier and more pest and disease resistant. And, most won’t need to be watered as often once they become established.

Some gardeners plant their yards exclusively with native plants, finding beauty in a carefree look that hasn’t been “tampered” with by horticulturists. A bed of native flowers may look unkempt at first, but even the most skeptical people soon learn to see the beauty of these plants—especially when butterflies and birds so obviously like them.

If you prefer the cultivated, showy look that makes hybrids so beautiful—symmetry, thickness, and more color choices—then go for it. Just be aware that some (not all) of these hybridized plants have lost the genetic traits that attract wildlife. Furthermore, some have now been genetically altered to contain insecticides. So check a plant’s tag before buying.

You can have the best of both by planting natives and cultivars! Just place hybrids in front of native plants to project the orderly, lush look you desire. Other options are to screen off an area behind a wildlife-friendly hedge or on an unused side of your house for natives. Above all, don’t eliminate them altogether—they’re preferred by wildlife. Be sure to check out other pages on this site that feature lists of plants suitable for an urban setting and urban wildlife.

Diversity and research

You’ll probably go through several plans before you decide on a final layout. Once you do, it’s time to be selective about plants. Diversity is a key to success because it benefits a broader range of species. For example, butterflies and honeybees need nectar flowers. Hummingbirds do, too, but they gravitate toward tube-shaped ones. Raccoons, Opossums, and birds need well-considered trees for resting, nesting, and hiding. Rabbits like tall grasses. Whether the habitat you’re creating is limited to flowerpots on your patio or covers an entire yard, diversity matters. How to protect from wildlife damage while promoting conservation

Many sources of information are available, including a local native plant society, garden clubs, the county agricultural extension agency, your state’s wildlife commission, your local library, bookstores, and the internet. Visit natural areas, like state parks, to see wildlife plants firsthand. Many of these places offer field guides for native plants and guided tours.

Select plant varieties that bloom and fruit at differing times of the year. Choose species that keep their berries or seeds into early fall, late fall, and winter. Some plants produce berries that are only eaten as a last resort—include some of those, too; they’re a safety net for tough times when everything else is gone (usually in late winter.)

New housing development?

If you’ve moved to a barren new housing development with few trees and plants, you won’t see a lot of activity initially. That’s all the more reason you should put time and effort into your yard. Think of it as an oasis in an urban desert. It’ll take patience, but more and more wildlife will visit as your yard develops, and you’ll see gratifying results. (If you can enlist your neighbors in a plan to make the entire neighborhood a habitat, so much the better.) You’ll be doing a very beneficial thing when you pour your financial and physical resources into a habitat for wildlife because they need it so badly.

Says Winnie-the-Pooh, in The Tao of Pooh, “Lots of people talk to animals,” . . . “Not very many listen, though,” 2 Well, you have listened! Take pride and enjoy your yard—the wildlife sure will!

*Top photo: King County, Washington / PD

1 About 54 million Americans use 800 million gallons of gasoline yearly to mow their lawns. Using one mower for an hour is equivalent to a hundred-mile automobile ride in a late-model car. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, altogether, mowers contribute as much as 5 percent of the air pollution in the United States.

2 1982, Dutton Books

More reading:

Designing paths, gardens for a backyard wildlife habitat

Nesting places for wildlife

Choose a birdhouse with these best features in mind

The basics

More landscape design tips