Jump down to: Background • Physical description • Tongue, Jaws, Fangs, Venom • Skin • Hibernation (Brumation) • Movement • Reproduction, Lifespan • Habitat, Foods, Digestion • Predators

Introduction

In a thriving backyard wildlife habitat, snakes will be around, and you’ll likely never see them. But should you ever cross paths, it’ll last only a moment: that snake will be just as startled as you. It’ll slither away as fast as it can because a snake’s primary method of confrontation is to avoid it. So please don’t harm it. Snakes are highly beneficial backyard wildlife.

When we can set aside our fears, we find that snakes are fascinating creatures that deserve respect. They help control populations of rodents and other pests and are themselves food for other wildlife.So, what is it that gives us the willies? Is it the unblinking stare? The scaly skin? The long, limbless body? Their slithery method of movement? The flicking tongue? All of that? Snakes scare nearly everyone—Dutch Bihary, a celebrity body paint artist who’s so masculine and muscular he looks like he could single-handedly take on a pit of vipers, says that the sight of a snake sends him running and “screaming like a little girl!”1 But, get this: little girls don’t scream and run! Neither do little boys. We might think human fear is inherent, but studies show that children don’t have a fear of snakes—they learn it from adults.2

Children aren’t naturally afraid of snakes. This girl is holding a Python. (© volodya.974 / Shutterstock)

Pet snakes seem to recognize their owners and show a preference for being handled by them rather than strangers. Some owners believe they like to be stroked, but basically, snakes can do without humans. (Snakes in petting exhibits must be “socialized” to tolerate handling by strangers.)

Background

Fossil evidence indicates snakes date back 143 to 167 million years, to the Jurassic Period when the world was relatively warm. It’s thought they evolved from burrowing and aquatic lizards because of anatomical similarities, including eyes without lids and no external ears. And, like them, they probably had legs back then, too. Both snakes and lizards belong to the scientific class Reptilia and the order Squamata, but snakes have their own suborder, Serpentes.

Today, about 2,700 species of snakes exist. They’re found all over the world except Antarctica. Around 120 of them inhabit North America, including twenty venomous ones.

Physical description

Snakes range in length from that of the Green Anaconda, Eunectes murinus, native to South America, which can be almost 19 feet long (6 m), way, way down to a 2008 discovery, the Barbados Threadsnake, Leptotyphlops carlae, only about 3.9 inches (10 cm).

In the United States, the Eastern Indigo Snake, Drymarchon corais couperi, is the largest native species at 8.0 feet (2.4 m) long. The Green Anaconda, Eunectes murinus, from South America and Trinidad, which has invaded Florida, can grow to 20 feet (6.1). Another non-native invader is the Burmese Python, Python bivittatus, from South and Southeast Asia, which grows to about 18 feet (5.5 m).

The smallest native snake in the U.S. is the Rough Earth Snake, Virginia striatula, only 7 to 10 inches (18–25 cm) long. An introduced species is even smaller, though. The Brahminy Blind Snake, Indotyphlops braminus, native to Africa and Asia, is so tiny at 4.0 inches (10.2 cm) long that it’s often mistaken for a worm.

In addition to body length, their skin color and patterning are markers for identifying snakes. They may be a uniform color, dull or bright, or have bold or subtle markings. Some snakes have colorful patterns of spots, bands, blotches, or stripes. Skin appearance is the same for both sexes and can’t be used to determine sex, but females are larger than males in 66 percent of snake species.

Eyes

There’s nothing remarkable about a snake’s vision except they don’t see colors. Their unblinking stare seems like a show of aggression, but, in reality, it comes from having no eyelids and eyeballs that fit tightly in their sockets, giving them limited movement. A transparent membrane called a brille covers their eyeballs to protect them.

Most snakes have round pupils, but an exception is a group of (primarily) venomous snakes known as pit vipers or vipers. These snakes have elliptical-shaped eyes with vertical pupils, giving them an alien appearance. This feature, however, can’t be entirely relied on to determine whether a snake is venomous. Cobras, taipans, and coral snakes are highly venomous but have round pupils.

There are two groups of pit vipers:

- First, venomous, nocturnal ones in the family Viperidae. They have a unique, heat-sensitive depression called a pit organ between the eye and nostril on each side of their head. These organs are sensitive to infrared thermal radiation—the heat given off by other animals—which gives them an edge when hunting prey in the dark of night. The pit organ can be seen in the Copperhead photo above.

- Second, non-venomous ones: Boa Constrictors and pythons, which belong to the family Boidae. They also have pit organs, but they’re smaller and located in or between the scales that line their upper and sometimes lower lip, usually three or more.

Ears

Snakes don’t have external ears. They also lack an eardrum and some of the other internal structures common to mammals. Instead, they have a small ear bone called the columella, which detects ground vibrations. It can also pick up sound waves transmitted through the air, but they probably don’t hear these sounds as well as humans can.

Nose

A snake’s nose has two nostrils through which it draws air. It’s the primary method of detecting smells, but not the only one.

Tongue

You already know snakes have a forked tongue and like to flick it furiously and repeatedly. It seems like a reptilian challenge, where they’re ready to take us on, dukes up! But, no. In reality—now, get this—they’re tasting us!

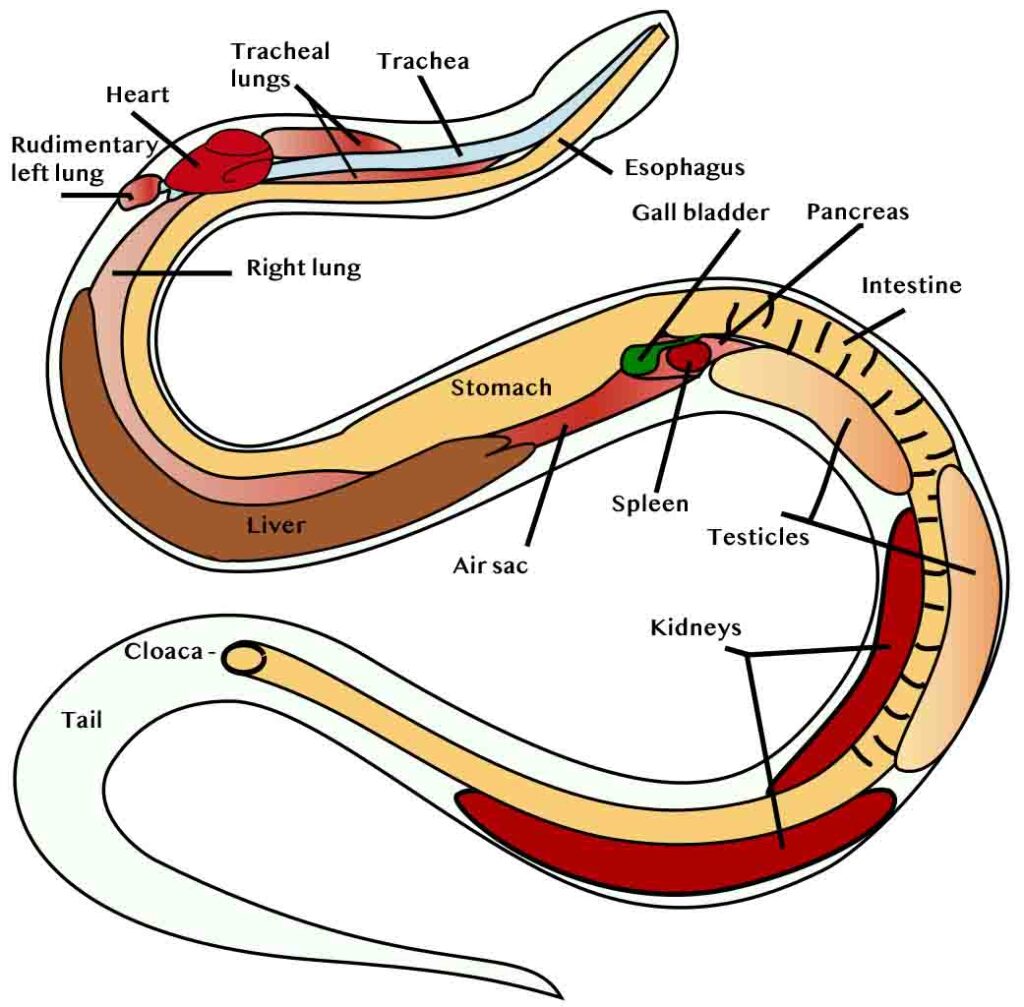

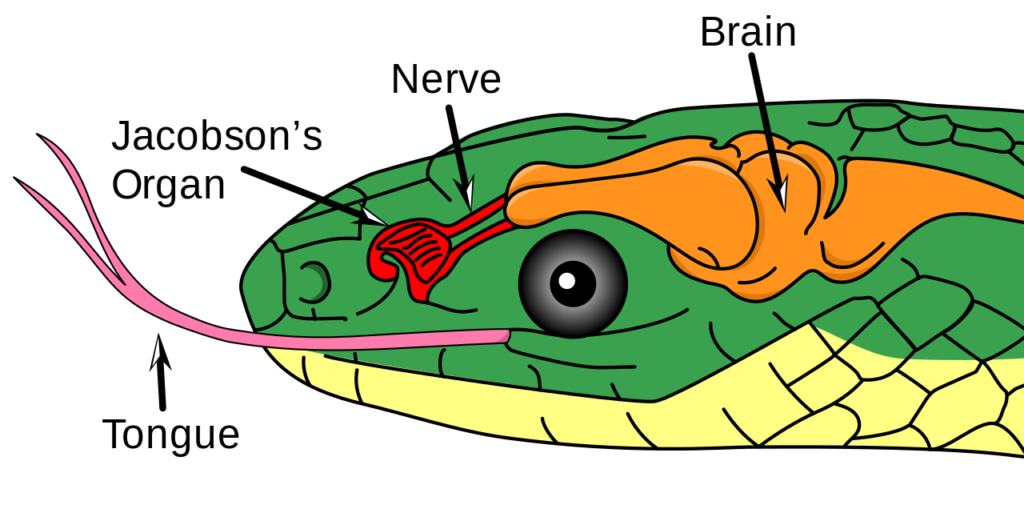

Yes, that “threatening” tongue is simply collecting samples of chemical molecules in the surrounding air for delivery to the vomeronasal organ, or “Jacobson’s Organ,” located on the roof of the mouth, where a human’s soft palate would be. (Humans have this organ, too, located in the nasal cavity above the roof of the mouth.)

Here’s what goes on, and it’s rather fascinating: The snake flicks its tongue out through its “lips” and wildly waves it around in the air to catch microscopic particles in receptors on its tongue. It then draws its tongue in and deposits those particles into the Jacobson’s Organ, where they’re sorted by chemical type and analyzed. Each receptor is specialized to receive a specific kind of chemical. It’s like a mini-lab in there! While this is going on, the tongue is already back outside, snatching more particles.

The amount of tongue-flicking is directly related to changes in the snake’s environment. When we approach a snake, we’re a perceived change, and the tongue shifts into overdrive.

The results of the chemical analysis are transmitted to the brain, along with other information gathered by infrared sensors located on the snake’s face. It arrives at an answer: Yummy, a big, fat rat is right over there! Or, oh, no, it’s a human, move away!

Jaws

Snakes have tiny teeth not used for anything but holding onto prey. They swallow their food whole—even managing to down those bigger than their own head.

A unique set of jaws makes this possible. Where a human’s upper jaw is fused to the skull, a snake’s is not. Instead, it’s held in place by muscles, ligaments, and tendons that give it a lot of mobility in all directions. The lower jaw is double-jointed, allowing it to dislocate when necessary. And, finally, the bones on the front of a snake’s lower jaw aren’t fused into a “chin,” like a human’s; instead, they’re held in place by muscle. Altogether, these features allow snakes to open their mouth up to 150 degrees!

Fangs, Venom

Most, but not all, snakes have fangs, which are long and sharp, and grooved or hollow teeth at the front or back of the upper jaw, depending on the species. With some, the fangs fold back when not in use. Only a few snakes are venomous. For example, Florida has fifty native species of snakes, but only six are venomous.

Venom is a toxin that immobilizes prey. It originates in a gland under each eye and flows via a duct through the fangs and into the prey’s body when the snake strikes it. Snakes can control the amount of venom they use and often don’t inject a full amount. How to keep yard safe from venomous snakes

Scaly Skin

Snakes are covered in scaly skin composed of keratin, the same protein that forms our hair and fingernails. Scales protect from abrasion and dehydration, give snakes their body color, and provide traction for movement. They’re not one-size-fits-all, however. Besides color, there are other differences: Some species have small, soft scales. Some have overlapping ones. Others are keel-shaped and appear rough. Snakes with smooth, shiny scales appear slimy, but they’re actually very dry. Scales on the top and sides are thinner and smaller than those on the bottom.

As a snake grows, its skin doesn’t grow along with it and eventually gets too tight, like our clothes do, if we gain weight. It wears out, too, so snakes of any age need to shed it periodically. Here’s how they do it:

The snake moves to a safe hiding place and stops eating. Its body secretes a fluid between a layer of inner skin and the outer skin, separating the two. It sheds its old, now-softened outer skin all in one piece by first rubbing its head against a rough surface to make it peel. Then, it crawls out, which can take several hours. Now, with beautiful fresh skin, the snake will remain hidden for a while longer. That’s because the brille (the transparent protective skin that protects the snake’s eyes) sheds along with the rest of the skin, leaving it visually impaired or even blind for a few days.

This process, called ecdysis, occurs as often as needed, from every three weeks to as long as once or twice a year. The faster the snake grows, the more often it sheds its skin. Snakes never entirely stop growing.

Cold-blooded

Touch a snake, and it’ll feel cool. That’s because snakes are cold-blooded and unable to generate body heat (ectothermic). Its body temperature is always the same as the surrounding air. So, if it’s 70 degrees Fahrenheit (21° C), that’s what the snake will be. Because humans have a relatively constant body temperature of around 98.6° F (37° C), a snake will always feel cool to our touch unless it’s been basking in the sun on a day that’s hotter than that. That isn’t likely to happen, however, because they prefer the mid-80s (26° C). They move in and out of the sun to regulate their body temperature. If the weather is too hot, they hide in a cool spot and remain inactive. When the temps start falling at the end of summer, they’re more likely to be seen because they’re “sunbathing” more often to warm up.

Hibernation (brumation)

Although snakes like to be cool, they don’t want to be cold, so those that live in cold areas “brumate” through the winter. “Hibernation” is the commonly used term for any animal that sleeps through the winter, but brumation is a metabolically different process and the technically correct word for reptiles. In this state, they sleep, but not deeply as in true hibernation, and occasionally stir. They don’t eat during this time.

Before brumating, they crawl below the frost line in such places as caves or holes in the ground, sometimes in large groups. (Garter snakes, with which most of us are familiar, are relatively cold-hardy and among the last to brumate in the fall.) Some snakes return to the same den year after year. In the spring, males leave their den first, and the females follow later.

Movement

Snakes are known for forming an S-shape as they move. As poet William Stafford put it, “When the snake decided to go straight, he didn’t get anywhere.” That’s amusing but not entirely true. They can use specialized muscles and the scales on their belly to give them traction to move in a straight line if they really, really want to. They have two other movements, too.

Eastern Ratsnake, Pantherophis alleghaniensis, climbing a tree (Richinpequea / Wikimedia; CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Serpentine: This is the S-shaped movement usually called “slithering.” The snake accomplishes this by contracting its muscles and thrusting its body side to side. This is the only one used in water (see the image at the top of this page).

- Rectilinear: This is a straightforward movement. The body moves through the action of three sets of muscles, including one within the belly’s skin, that propel it forward. Watch a video of this

- Sidewinding: With this, the snake contracts its body and flings it sideways. It’s common in habitats with loose sand, like deserts.

- Concertina: A snake can climb by using this method. It moves its head forward, then bunches up the middle and clings tightly while pulling up the tail end. Following that, it springs forward to get a new grip with the front end. And so on.

Reproduction

Mating usually occurs in early spring as temperatures begin to warm, although some snakes mate in the fall. There’s a frenzy of activity as males follow pheromone trails left on the ground by females. Sometimes, dozens of males will try to wrap themselves around a single female, forming a “mating ball” as each tries to be the successful suitor.

In calmer situations, where there’s a single courting couple, a male begins by crawling all over the female and bumping his head on the back of hers or flicking her body with his tongue. He aligns his body with the female and wraps his tail around it. When she’s ready to accept him, the female raises her tail to expose her cloaca (klo-A-kuh), a multipurpose posterior opening through which intestinal and urinary matter exit the body and where copulation also occurs.

Anatomically, males are doubly endowed. They have two sex organs, called hemipenes, although only one is used at a time in mating. (They’re hidden away when not in use.) Mating usually takes place once a year. After mating, males leave with the ambition of finding more females before the season is over.

Eggs and live birth

Some snakes are oviparous (egg-laying), and others are viviparous (live birth).

For snakes that lay eggs, the time between mating and laying them is normally one to two months, depending on the species. A snake that’ll hatch from an egg has a bump, called an egg tooth, on the front of its jaw that curves forward in front of the snout. The edge of it is flat and very sharp, and when the right time comes, it’ll be used to slice the shell open. The egg tooth will disappear later on. The eggs, leathery-shelled and numbering up to a hundred (or 150 in the case of some viviparous species), are usually laid in early summer in a spot that will provide protection and moisture. Once laid, the mother gives her eggs no attention—they and the babies that will hatch from them are on their own (a few exotic species, like pythons, will guard their eggs for a few days). Some viviparous species produce up to 150 babies.

Baby snakes have a name

There’s a name for baby snakes. Newborns (live births) are called neonates, while newly hatched are called hatchlings. When they get a bit older, snakes are called snakelets. New ones range in length from 3.0 to 17.0 inches (7.6–43 cm), depending on the species. They’re miniature versions of adults and can start hunting immediately. They grow quickly at first, then slow down considerably after maturity.

Lifespan

Snakes live ten to forty years, depending on the species.

Habitat

There are four types of snakes: arboreal (tree-dwelling), fossorial (burrowing), terrestrial (ground-dwelling), and aquatic. Most are considered terrestrial, even when they spend much time in trees, underground, or water. Snakes are found nearly everywhere: parks, meadows, woodlands, mountains, grasslands, swamps, marshes, deserts, and urban yards. They like a warm climate and prefer temperatures no lower than about 65° F (18° C). Some like deserts, but a brook or pond with lots of cover around it attracts the most.

In urban areas, snakes hide in untrimmed shrubs, woodpiles, debris piles, rock piles, deep mulch, crawlspaces, under porches and sheds, and in basements with a rodent problem. Summertime finds them seeking cool, moist places. In winter, they brumate below the freeze line.

Food sources

Snakes use hearing, sight, taste, and ground vibrations to locate food. In the case of pit vipers, they also use their infrared, heat-detecting pit organs. Species may use one sense more than others, depending on their lifestyle.

All snakes are carnivores, and they’re doing us a favor when they visit our yards because rodents are high on their list of delicacies. They also gulp down vast quantities of insects, other reptiles, and just about anything else they can swallow, including a gardener’s pet peeve—slugs. Smaller snakes eat smaller prey. Most eat once a week to once a month. The frequency depends on the availability and size of food. That said, not all snakes eat all things. For instance, some species seek out eggs or snails only. There are some that feed on worms and insects.

Snakes can swim very well and search for some of their prey in or near water. Since their eyes and nose are at the top of the head, they can see and breathe while swimming.

Digestion

Snakes eat their food whole. Potent digestive enzymes break down the entire body of their prey, including the bones. Some can eat up to one hundred percent of their body weight in one meal! After eating, they raise their body temperature to speed up digestion. Since they’re cold-blooded and can’t accomplish that without help, they may sunbathe, lie under a warm rock, or even extend into the sun only their body section that contains the digesting prey while staying otherwise hidden.

Predators

Snakes are prey for birds, skunks, opossums, raccoons, fish, other reptiles, minks, ferrets, and house cats. Their most significant threat is habitat loss. Humans take a toll on them, as well.

Simply let them slither away

Snakes want to escape from humans and will quickly do it, given a chance. A cornered snake will be frightened and express it by hissing and shaking its tail. (The shaking tail may rustle nearby brush and sound like the rattles of a rattlesnake—many harmless snakes are killed because of this.) Because it’s trapped, the snake may advance as a bluff to try to scare the individual away. If that fails, it may eventually strike. A snake can lunge forward about half the length of its body. When encountering a snake, just slowly move out of its way and all will end well for each of you.

1 “Skin Wars,” S1 E4, American Game Show Network, August 27, 2014.

2 Vanessa LoBue, Karen E. Adolph, “Fear in Infancy: Lessons From Snakes, Spiders, Heights, and Strangers,” NIH National Library of Medicine, September 1, 2020, https://bit.ly/3qJ6WIg

More reading:

Snakes: frequent questions

Proper rescue, care for injured or orphaned urban wildlife

For this snake, ‘rough’ takes on new meaning