“Butterflies are not insects . . . They are self-propelled flowers,” writes Robert A. Heinlein in his book, The Cat Who Walks Through Walls. Graceful, beautiful, non-threatening heralds of spring and summer that they are—who doesn’t admire them? We’d see that moths are all these things, too, if only they’d step out of the shadows where they mark time during long sunlit days. Day or night, these insects represent nature in its most peaceful expression. Learn all about butterflies and moths and the fascinating lives they lead.

Jump down to: Background • Differences butterfly, skipper, moth • Physical characteristics • Head • Thorax • Abdomen • Senses, Communication • Behavior • Mating, Eggs • Larva • Pupa • Adult • Lifespan, Foods • Habitat, Predators, Defenses

Background

Butterflies and moths belong to the order Lepidoptera. Moths don’t get the attention that butterflies do, but they comprise the vast majority. Butterflies are known to experts by their suborder, Rhopalocera, and moths by an unofficial name, Heterocera. Skippers are a family, Hesperiidae, of butterflies. Lepidopterans are known to be ancient, but a fossilized moth’s wing found in Germany in 2018 reveals they’re even older than scientists realized. The oldest one found so far, it dates back 200 million years to the early Jurassic Period.

“Lepidoptera” (Lep-uh-DOP-ter-uh) comes from the Greek libido, meaning scale, and ptera, meaning wings. “Moth” comes from Middle English mothe, which in turn came from Old English moththe. “Butterfly” dates prior to the 8th century and was originally a combination of the Old English words butere (butter) and fleoge (fly), but how did it come to get that name?

“Butter-fly.” No one really knows what possessed people back in the eighth century to combine those words. A popular theory is that a subfamily of butterflies called sulphurs, or yellows, were once called butter-colored flies (in particular, the Brimstone Butterfly, Gonepteryx rhamni), and this eventually expanded to include all butterflies. Another is that butterflies were thought to steal buttermilk and earned their name that way..

Number of species, distribution

Lepidoptera is a large order, second only to beetles in the number of species that have so far been described by entomologists. Lepidopterans inhabit all continents of the world, except Antarctica. There are about 17,500 species of butterflies and 160,000 species of moths. The continental United States has around 750 species of butterflies and 11,000 species of moths.

Butterflies are beneficial

From the perspective of farmers, some gardeners, arborists, and other affected parties, Lepidopterans, mostly moths, are destructive because their caterpillars destroy crops. On the other hand, they also feed on weedy plants we’re glad to be rid of, and they’re pollinators. They’re also an important food source for numerous wildlife.

Size

Butterflies range in size from 0.5 to 0.8 inches (13–20 mm), which is the wingspan of the Western Pygmy Blue, Brephidium exilis, found in the southern US and elsewhere, up to the 12 inches (30 cm) of a rare Papua New Guinea rainforest species called Queen Alexandra’s Birdwing, Ornithoptera alexandrae.

Western Pygmy Blue Butterfly, Brephidium exilis, world’s smallest butterfly. (Katja Schulz / Flickr; cc by 2.0)

Moths in the Nepticulidae family are even smaller than the smallest butterflies, by quite a bit, with a wingspan of only 0.1 inches (0.3 mm)—shorter than a grain of rice. The biggest moth is the beautiful Atlas Moth, Attacus atlas, of Southeast Asia. It has a wingspan of 9.8 to11.8 inches (24–30 cm)—the same as the American Robin bird.

To the unpracticed eye, butterflies, skippers, and moths may seem much alike. And they are. But they also differ externally in ways that make each group identifiable from the other two. Here’s a chart to help you.

Differences between butterfly, skipper, moth

| True Butterfly | Skipper | Moth |

|---|---|---|

| Usually brightly colored | Usually dull orange, tan, gold, or brown | Usually drab: brown, gray, black, white, or combination; often a camouflage pattern |

| Body slender, smooth, generally larger | Body smaller, stout | Body smaller, plump, hairy, or funny-looking |

| At rest, wings usually held upright and together | At rest, forewings upright and together and hindwings held horizontally | At rest, wings held flat out to the sides or folded atop the body |

| Antennae thin, with club-shaped tips | Antennae thin, with clubbed and hooked tips | Antennae feathery or comb-shaped, or filamentous and unclubbed |

| Active in daytime | Active in daytime | Active at night |

(Note: To make wording less repetitive, from here on “butterfly” will be used as an umbrella term that includes skippers and moths, since they are all more alike than different. Important differences will be noted.)

Physical Characteristics

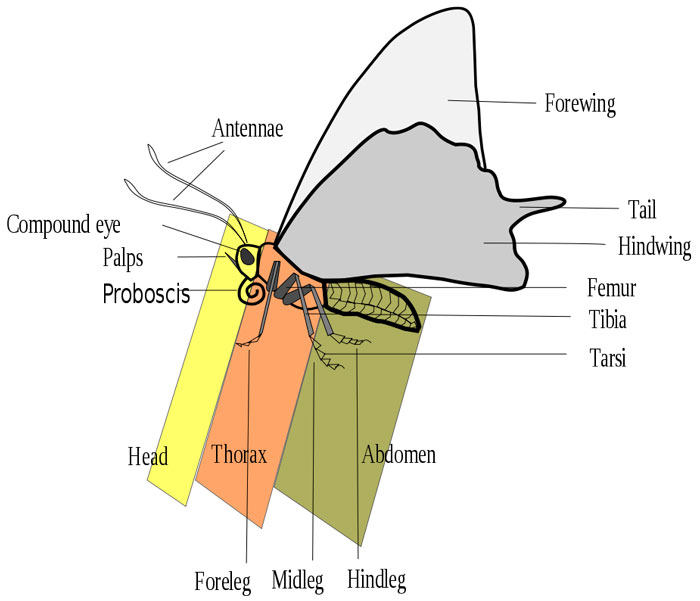

Butterflies, like all insects, have three main body parts—head, thorax, and abdomen. They have two large compound eyes, three pairs of legs, and two pairs of wings.

The head, thorax (including the wings and legs), and abdomen have scattered hairs, as well as a thick covering of scales pigmented with such compounds as melanins and flavones that produce orange, yellow, and black shades. Scales on the wings have a microstructure that reflects blues and purples, as well as white. The top (dorsal) and bottom (ventral) sides of the wings are often very different from each other but may be equally beautiful.

The Essex Skipper, Thymelicus lineola, in a typical skipper position. (© Khort Esther Tatiana / Shutterstock)

True butterflies are often brightly colored, sometimes even in brilliant metallic tones. Skippers are drabber, usually wearing dull-orange, tan, gold, or brown colors. Most moths are drabber still—brown, gray, black, white, or a combination—often with a camouflage pattern to help hide them from predators in the daytime.

Males and females can be hard to distinguish from each other. But, generally, females are larger, with a fatter abdomen. And, the color and pattern of wings can differ.

Head

The head has a brain, two compound eyes, two simple eyes, two antennae, a proboscis and other mouthparts, palps, the beginning of the digestive system, and nerve ganglia leading to the rest of the body.

Eyes

Butterflies have two kinds of eyes: compound and simple.

The compound eyes, one on each side of the head, are large and oval. They aren’t moveable, but a nearly 360-degree field of view easily compensates. They’re composed of thousands of individual lenses, called ommatidium, each of which sees its own tiny portion of an entire picture, which the brain interprets. Their vision isn’t particularly acute, because it’s fixed, but it’s especially adapted for the detection of movement. There’s no sneaking up on these guys; they see you approaching, even if they don’t immediately fly away.

Butterflies have color vision and use it for finding flowers. They see polarized (reflected) light, as well as ultraviolet, which is a high-frequency spectrum that produces colors and patterns invisible to humans. Females of some species also seem able to distinguish plants by the shape of their leaves.

Adult butterflies and (almost all) adult moths have two simple eyes, called ocelli—one is located just above each compound eye. They’re tiny (often hidden from view), with a single lens that can detect only light and dark, unable to form an image. All caterpillars lack compound eyes and have only simple eyes.

Microscopic view of the head of a moth in the Pyralidae family, showing its compound eye composed of many lenses, and proboscis. (Dartmouth.edu / Wiki; PD)

Antennae

The antennae extend out from between the eyes. They can be moved independently of each other and into many positions. They’re segmented and covered by thousands of either hair-like or scale-like sensors for detecting pheromones (Monarchs have up to 1,370,000 of them!) The tips of the antennae can also taste the chemical qualities of soil or other matter. At the base of each is the Johnston’s organ, a collection of nerve cells that sense orientation and balance during flight, and, it’s thought, may detect magnetic fields.

Mouthparts

The mouthparts of adult butterflies are designed for siphoning liquids. What’s particularly noticeable about them is the curious tongue, or proboscis—it’s tube-shaped and functions as a straw. Kept tightly coiled when not in use, it’s rolled out when sipping nectar from flowers. Proboscis length varies; the depth of a flower’s nectar tube determines what kind of butterfly will feed from it. A labial palpus is located on each side of the proboscis. Covered with scales and sensory hairs, they’re used for tasting foods. They may also help to shield the proboscis from injury.

Caterpillars have mandibles (jaws) for eating leaves and other plant parts. They disappear during pupation, or nearly so, which limits adults to a liquid diet. A few moth species, as adults, have no mouthparts and don’t eat.

Thorax

The thorax is the middle part of the butterfly’s body. Attached to it are six jointed legs, three per side, and two pairs of wings. Each leg has a foot with taste sensors and a claw at the end for clinging. In some families, the front pair of legs is nonfunctional and kept folded.

The wings are thin, delicate, and covered by millions of overlapping scales. Touch them and they’ll easily rub off into a powdery “dust,” exposing an underlying transparent membrane. In some species, the body also has scales.

The wings couldn’t function without a network of stiff veins to give them structural support, and they’re surprisingly strong. They can hold up over hundreds of miles, growing ever more torn and tattered before they finally fail. The Painted Lady Butterfly, Vanessa cardui, reportedly can migrate over 600 miles before stopping to rest, its wings still functional! At least one species of moth, a cutworm moth, travels 99 miles nonstop (159 km) over water.

Butterflies can beat their wings at eight to 12 times per second, depending on the species, and fly up to 37 miles per hour (60 km/h), which skippers do. As for flying altitude, look up. Way up! Migrating Monarchs have been spotted at 11,000 feet (3 km)!

Abdomen

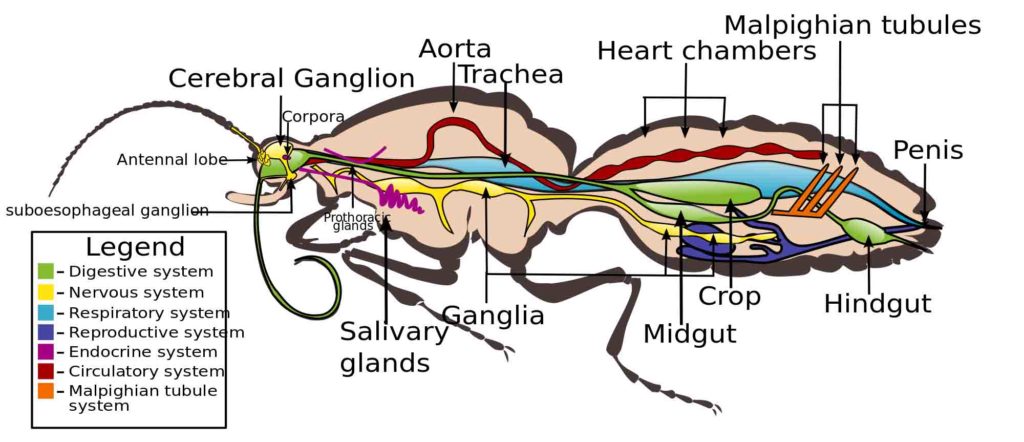

The abdomen is the longest part of the body. It contains the circulatory, respiratory, and excretory systems, as well as the tail end of the nervous and digestive systems, which originated in the head. And, the sex organs.

Circulatory system

A butterfly’s “blood,” like that of all insects, is called hemolymph. It’s a fluid that contains nutrients, salts, hormones, and metabolic wastes, but not oxygen. And, it isn’t red, because it lacks the iron-rich hemoglobin that gives color to our blood. Also, unlike our’s is its “heart,” which is a long tube called the dorsal vessel, which extends from the abdomen through the thorax to the head.

The dorsal vessel pumps hemolymph forward (one-way valves prevent it from flowing backward), where it floods the head, legs, and wings. From there, the fluid simply flows backwards throughout the thorax and into the abdomen, bathing all the organs along the way. Nothing constrains it, there are no vessels or veins. This is called an “open circulatory” system.

Respiratory system

Butterflies breathe passively through a process called rhythmic tracheal compression. Movement of the body causes tiny pores, called spiracles, which are located along the sides of the abdomen and thorax, to draw air in and move carbon dioxide out.

Senses

Butterflies have five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch.

Sight: Adults have large compound eyes that deliver a good impression of what’s around them, but their vision is blurrier than that of a human. They also have simple eyes that detect only light and dark. Caterpillars have only simple eyes on each side of their head.

Hearing: Butterflies don’t have ears, but they do have organs that detect sound waves. Moths, which are nocturnal, are especially attuned to the high-frequency echolocation of bats hunting for insects at night.

Smell: A butterfly’s legs and feet are loaded with olfactory organs, but their antennae are the masters at smell detection, containing as many as 1,370,000 olfactory scales, hairs, and pits. Some male moths that have feathery hairs on their antennae can smell the potent pheromones of females 3 to 4 miles away (5 to 6 km).

Taste: Both adults and caterpillars have sensory organs located on their antennae and feet that can taste foods and distinguish between what to eat and not to eat. Also, some females taste plants with their feet to determine if they’re suitable for laying their eggs.

Touch: Butterflies sense touch through tactile setae. These are hairs attached to nerve cells.

Communication

Communication is mostly through pheromones. A very few butterflies and moths make sounds. For instance, male Cracker Butterflies, Hamadryas spp., indigenous to South America, make clicking noises with their wings during territorial disputes. The male Asian Corn Borer Moth, Ostrinia furnacalis, an Asian species, emits an ultrasonic “chirp” during courtship, by rubbing his wings against his thorax. Highly territorial males of some species communicate with intruders by chasing them away.

Behavior

For butterflies, daytime hours are spent looking for mates, mating, depositing eggs, finding food, and periodically resting. Most moths do all that at night and rest in the daytime.

Butterflies are cold-blooded, meaning they lack the internal mechanisms for generating heat and, therefore, are the same temperature of their surroundings. Their body core functions in colder temperatures, unless it’s freezing, but they must have heat to warm their muscles for flight. They solve this problem by basking in the sun to absorb its warming rays, their wings outstretched. If the day isn’t quite warm enough, they shiver to help generate body heat. If it’s just too cold, cloudy, or rainy, they won’t fly at all. They also hunker down when it’s too windy.

Moths, mostly nocturnal, solve the problem of warming up in a couple of ways. They can shiver, but they also wear a coat—in the sense that they have a thicker layering of scales than butterflies (this gives them a furry appearance).

Resting behavior

When butterflies rest, their metabolic rate slows down and they relax, but they don’t sleep. They hang from the undersides of leaves to rest, shelter from rain, and hide from foraging birds. Or, they may tuck themselves, day or night, into such sheltered places as crevices in rock piles, in woodpiles, behind loose tree bark, or a tiny crack between a door and its frame.

Moths are so well hidden by their camouflage colors that they may cling to a tree trunk or lie on the surface of a leaf in full sight. Wherever they are in the daytime, most will be hard to see. Butterflies and moths can rouse themselves immediately and fly away if disturbed.

Butterflies don’t urinate or defecate. A bit of red liquid, called meconium, is expelled from their anus when they emerge as adults, but that’s metabolic waste left over from their metamorphosis.

Moths and porch lights

Diapause

Life cycle

Butterflies undergo complete metamorphosis, which means that each generation develops through four life stages: From egg to larva to pupa to adult.

Mating and eggs

Males and females find each other through pheromones, wing coloration, and with a very few, sound. They may perform courtship displays of simple to elaborate flying maneuvers before coupling, end to end, on the ground or in the air. Mating can last from minutes or, like the Monarchs, up to hours. Depending on the species, fertilized females may carry less than a hundred eggs up to more than a thousand. Eggs may be deposited singly or, like Gypsy Moths, in masses of thousands.

Host plants

Butterfly caterpillars, or larvae, hatch from eggs laid on a “host” plant (some moths deposit their eggs on the ground near plants). Whatever the mother chooses will be one her young will eat—some moths are less picky, but most larvae will starve to death rather than eat from the wrong plant. (For this reason, it isn’t a kindness to relocate a caterpillar, except to the same kind of plant.) How does the mother determine the right one? She tastes it with sensory organs on her feet. What if she can’t locate one? Then, she’ll hold her eggs until she does.

Host plants vary widely. For example, Monarchs use milkweed plants exclusively, even though they’re very bitter. Black Swallowtails like the foliage of parsley and carrot plants. The Mourning Cloak Butterfly and Polyphemus Moth eat the leaves of mulberry, willow, birch, oak, and other trees. The Virginia Creeper Sphinx Moth eats, yes, Virginia Creeper leaves.

Photos of a larva hatching

Larva

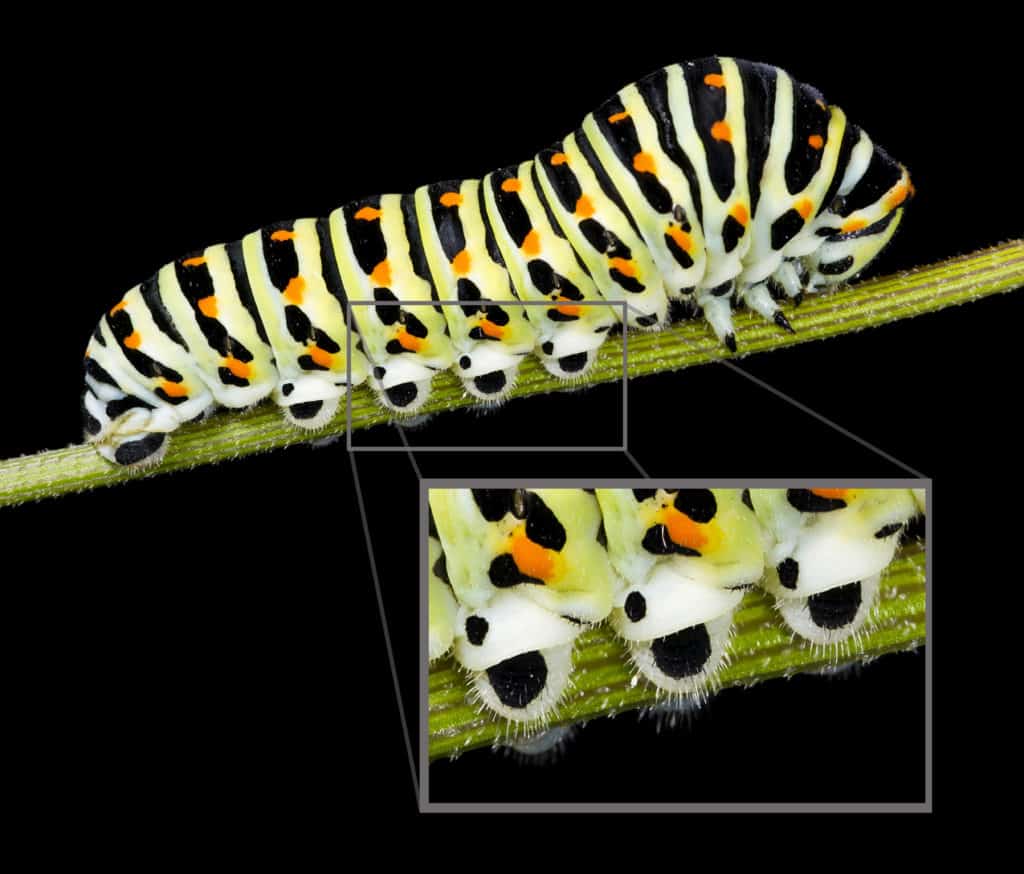

Larvae are slow-moving and have long, segmented bodies. They have a brain, chewing mouthparts, antennae, and other internal organs, but no eyes. Instead, they have three pairs of ocelli on their head. Spiracles, through which oxygen enters and carbon dioxide is expelled, run along the sides of their body. Most larvae have legs; the number varies with the species, but typically it’s three pairs of true legs and five pairs of prolegs. The true legs have joints and are located on the thorax; they’ll later become the adult’s long legs .

The prolegs are temporary. Fleshy and stubby, they’re located along the abdomen and near the rear end. Used for grasping stems and leaves, and to help the larva move, they disappear during metamorphosis.

Larvae diet

The sole mission of larvae is to eat and grow big, and there’s a lot of variety to what they eat. They’re herbivores, with one exception, those of the Harvester Butterfly, which eat woolly aphids. Usually, they begin by devouring their eggshell, which has vital nutrients. Following that, they start in on the leaves and sometimes the flowers or other parts of their host plant—usually a flowering variety or a conifer’s cones, fruits, or seeds. Mosses, ferns, liverworts, and other kinds of flora are eaten by a few. Flour moths, Ephestia spp., eat grains. The larvae of clothes moths eat the natural fibers of clothing.

Larvae eat almost constantly for around two weeks to a month. They grow astonishingly fast, faster than any other animal in the world. For example, the Tobacco Hornworm, which will become a Carolina Sphinx Moth, Manduca sexta, grows 10,000 times bigger within about 20 days.

Usually, there are only a few eggs per plant, as their mother won’t put them all in one basket, as the saying goes. This is to ensure that a plant will be enough food for the larvae placed there. And, it increases the odds that other offspring will survive if a particular plant’s larvae are destroyed by predators.

Kinda cute, but painful to touch. The Saddleback Caterpillar, Acharia stimulea, is a moth that’s native to eastern North America. (Katja Schulz / Flickr; cc by 2.0)

Regardless, many larvae won’t make it to the next stage of their lives. As Daniel H. Janzen, professor of biology at the University of Pennsylvania, says, “Caterpillars are food for almost every carnivore. That means birds, mammals, spiders, beetles. Everybody eats caterpillars. So it’s a sort of hamburger in the world.”

Larvae defense strategies

Although their life is fraught with danger, they have some defense mechanisms. Some have color patterns near their back end that look like eyes—meant to stare and scare—to ward off timid predators. Some are colored to match their host plant. Others have spiny bristles or hairs that irritate anything that brushes against them (including a human’s skin). The jaunty-looking moth caterpillar above (Sibine stimulea) has barbed hairs that secrete a venom when touched. Some species spit acidic juices or, like Black Swallowtail Butterflies, discharge an offensive odor. There are even larvae in SA that have venom glands. Some, like the Monarch, are protected from predators because the plants they eat make them distasteful or even toxic.

Molting

The skin of larvae can stretch to accommodate some of their growth, but it has its limitations. When the time comes, it’ll be shed (molted), with the larva crawling out headfirst wearing a new skin. They molt as many as four or five times, depending on the species, and there is a name for each larval stage: instar. When larvae first hatch they are tiny caterpillars referred to as “first instar.” After they shed their skin for the first time they become a “second instar,” and so on.) Their skin may change in appearance from one molt to the next.

When a brain chemical called juvenile hormone is at a certain level, larvae undergo their final molt and eject the contents of their digestive tract. At that point, most leave their host plant and look for a suitable, safe spot to enter the next stage of their lives, pupation.

Pupa

Author Maya Angelou wrote this in a different context, but it’s so fitting here: “We delight in the beauty of the butterfly, but rarely admit the changes it has gone through to achieve that beauty.” Readying for pupation is just the first of the larva’s many struggles. Monarchs must deposit silk from a gland in their lower lip to create a pad that a hook located at the rear of their body can attach to. Called a cremaster, it takes much twisting and turning to lodge it firmly—this is important, as the larva will be suspended head down from it. Others, such as Black Swallowtails, must create a silk sling to support their bodies in a head up position from a twig or branch.

Once a larva is anchored, it must, with great force, break out of its skin to expose its chrysalis (KRIS-uh-lus), a new layer of skin within which it will pupate. After taking a short, well-deserved rest, it begins to transform. Its body mostly liquifies into what some scientists call a “nutrient soup” of pre-programmed cells that had lain dormant. But, now active, they begin to form the different parts of an adult’s body. (Most skippers go through this process after wrapping themselves in a nest of leaves stitched together to form a cocoon. Most moths go underground, or like some sphinx moths sometimes do, crawl into rock crevices. Moths that find their way indoors, such as clothes moths, look for a crack to crawl into.)

Adult stage

Metamorphosis, which is both magical and wonderful, usually takes about ten days to two weeks. The new adult, called an imago (em-AH-go), is a pathetic sight at first. Its abdomen is large, full of fluid. The wings are all wet and crumpled up, looking utterly useless. Actually, they are. But, the imago has a solution for that little problem—literally. It begins to pump body fluids from its abdomen out into its wings.

Little-by-little, the abdomen gets smaller while the wings unfurl and take on shape, strengthened and plumped by the fluid. The butterfly turns its wings to the sun to grab its heat and to dry, and it flaps them to build muscle. These are life or death moments for the imago. If anything—even a twig or leaf—prevents its wings from taking proper form, they’ll be useless, leading the poor butterfly to death by starvation or predators.

Time-lapse of a Viceroy Butterfly, Limenitis archippus, (not a Monarch, although very similar) emerging from chrysalis (© Kathy Keifer / Shutterstock)

Finally, when its body is ready and the time is right—and with its mind on food and finding a mate—it takes to the sky, as though it has done it a hundred times before. No apparent wobbling, no crashing into a tree, nor a nosedive into the birdbath.

Lifespan

Most species will live a few days or a few weeks as adults, with the average being around two weeks. Some live for several months. A notable example is the Monarch, which emerges in July or August of one year, moves south to central Mexico, and then migrates north again the following spring to lay eggs before dying. Monarch life cycle pictorial

Food sources

Most adult butterflies drink nectar, but a few species feed on sap, fermenting juices of rotting fruit, bird droppings, or dung. Some supplement their diet by visiting mud puddles to drink up the nutrients and salts in wet soil. A few moth species don’t eat at all as adults.

Depending on the species, larvae eat nearly all parts of a plant—usually a flowering variety or a conifer’s cones, fruits, or seeds. Some, like flour moths, Ephestia spp., eat grains and can become pests. Mosses, ferns, liverworts, and other kinds of flora are eaten by a few. Attract more butterflies with native nectar plants

Habitat

Butterflies and moths live nearly everywhere—gardens, fields, roadsides, wetlands, forest edges, mountain tops, canyons, even deserts.

Predators and defense strategies of adults

Butterflies are prey for spiders, wasps, birds and other wildlife. Most of the brightly colored ones are distasteful to predators. It’s thought their coloration has evolved as a successful visual warning not to touch them, because it seems to work. They have a nasty taste that comes from the juices of certain host plants eaten by them during their caterpillar stage. The Monarch is one example: Their larvae feed on milkweed, the juice of which is bitter and mildly toxic, and both larvae and adults are avoided by knowledgeable predators. Black Swallowtail Butterfly and Wood Tiger Moth larvae are among those that emit a repulsive odor. Some moths have patterns or eyespots on their wings meant to confuse or intimidate predators. Most have camouflage patterns that simply hide them in plain sight on the background they’re clinging to.

The camouflaged moth is seen from its right side, hanging head down. Its wings are folded into a tent shape, and there’s a dark brown horizontal line across the middle of them. Look for the small brownish-red circle near the bottom, which is its eye.

More reading:

Dragonflies and damselflies – “Top Guns’ of the insect world •

Where are they? Answers to the mysterious disappearance of summers’ wildlife •

Think all moths are drab? These will change your mind •

Attract butterflies to your yard • America’s favorite butterflies • In your yard: beautiful moths