There are three raccoon species¹ in the world. Here in the United States, we’re lucky to have one of them, the Northern Raccoon. This clever and handsome critter probably visits your yard every night, foraging for rodents and reptiles and any tasty leftovers you’ve added to your compost bin.

Background

The Northern Raccoon’s scientific name is Procyon lotor. Procyon comes from Latin-Greek for “before dog,” and lotor is Latin for “washer,” a reference to the Raccoon’s reputation for washing food. Most sources say the word “raccoon” comes from Algonquin Indian arakun, meaning “one who scratches with his hands.” Wikipedia.org relates it to the Powhatan Indian words aroughcun and arathkone.

| Class: Mammalia |

| Order: Carnivora |

| Family: Procyonidae |

| Genus: Procyon |

| Species: P. lotor |

Raccoons are mammals in the Procyonidae (PRO-sy-ON-O-dee) family, which originated in Europe. Their oldest fossils date to the Oligocene (OLLY-GO-seen) Epoch, 25 million years ago. Discovered in Europe, analysis of them shows a common ancestor with weasels but a closer relationship to bears. At least six million years later, their then-existing ancestors crossed the Bering Strait from Russia into North America.

Today Northern Raccoons and their subspecies are found across the continental U.S., much of Canada, Mexico, and Central America. Although native to North America, they now inhabit much of Europe and Japan.

Physical description

The Raccoon’s most distinctive feature is its “bandit’s mask,” a covering of black hair around its eyes reminiscent of an Old West outlaw’s mask, framed by white “eyebrows” and a white snout. They often have a brown-black streak extending between their eyes from the forehead to the nose. The rest of the body is covered by a mix of dark and light hair, which helps them blend into the dappled light of their forest habitat. About 90 percent of their hair is a thick undercoat which they start shedding in late winter. A long, bushy tail with several dark rings is another distinction.

Size

Raccoons are 16–28 inches (41–71cm) long, not counting their tail, which is about 10 inches (25 cm). At the shoulder, they stand 9–12 inches (23–30 cm). They weigh 14–30 pounds (6–14 kg), about the same as a Boston Terrier dog. Males are larger than females.

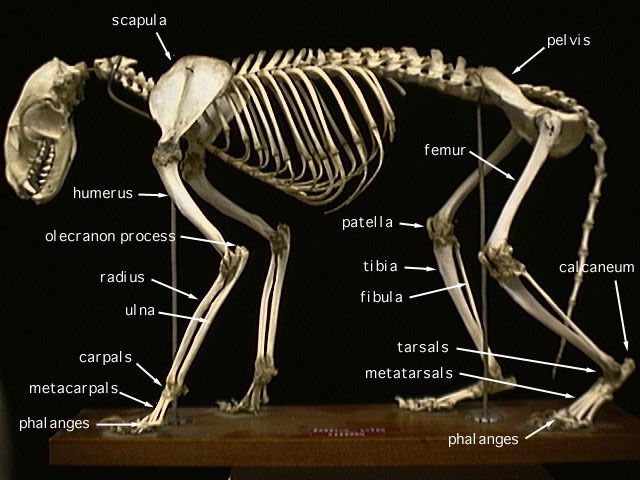

Raccoon skeleton on display at Museum of Zoology, Univ. of Michigan (Phil Myers / EOL; CC BY-SA 3.0.)

Agility

Raccoons have five hairless, claw-tipped fingers and toes. Their front paws are unique because they have thumbs. Not opposable ones, like a human’s, but they’re second only to a monkey’s in dexterity, and their handprints look remarkably like tiny human ones. If they get inside a house, their nimble fingers can turn a doorknob, open cabinets, drawers, the refrigerator, and unscrew jar lids! Their natural curiosity will lead them into every nook and cranny.

They’re agile climbers that can come down a tree both forward and backward and have been known to drop forty feet (12 m) without injury. They usually walk on all fours but can easily stand on their back legs. They’re also good swimmers. Raccoons typically move in a slow, shuffling manner, but they can run surprisingly fast, if necessary, up to 15 miles per hour (24 km/h).

Senses

As you might guess from their fondness for feeling food, the Raccoon’s most important sense is touch. In fact, almost two-thirds of the part of their brain that deals with sensory perception is specialized for touch impulses. As for their other senses, they have excellent night vision, but poor distance vision, and they’re believed to be color blind. Their sense of smell is keen, and their hearing is, too.

Intelligence

Raccoons are very intelligent. A Vanderbilt University study showed they have about the same number of neurons in their cerebral cortex as dogs. Other research has shown they can remember puzzle solutions for at least three years. To escape hunters, they’re smart enough to cross a stream and double back, climb trees and jump from tree to tree, or enter water and swim downstream to break their scent trail.

There’s a cute Northern Raccoon, “Melanie,” who lives in Europe, with a repertoire of 100 different behaviors and tricks, including somersaults, using a broom, riding a bike, a scooter, and a skateboard. You can watch Melanie here.

Communication

Raccoons are reported to have 51 vocalizations. They growl, hiss, scream, screech, and whinny. When they fight, they sound something like wrangling cats. Baby raccoons make mewing, twittering, cooing, and crying sounds of varying intensity depending on their level of stress or joy. Researchers also believe Raccoons’ distinctive coloration enables them to communicate through facial expressions, and their light-and-dark-banded tails may also help them quickly interpret one another’s posture.

Behavior

Raccoons are mild-mannered and prefer to run from conflict, so they’ll try to move away. However, if forced to fight, they’re fierce and strong. They’re nocturnal, roam an extensive home range at night as they search for food, and, if it’s scarce, they may cover several square miles. If you see one out in the daytime, it’s probably a nursing mother in need of extra nourishment.

Initially considered territorial loners, there’s some new evidence that related females will share an area, and up to four males will live together during mating season to defend their turf against others. Still, if you see a group, it’s most likely a mother and her youngsters.

Food washing

Raccoons like to manipulate and feel food. They’re known for “washing” it, but it’s more accurate to call them food “wetters.” They don’t always do even that. When they do, it isn’t to specifically clean it–they just like to dabble, which also happens to soften the food.

Raccoons spend the winter sleeping (not hibernating) in their dens, especially those living in more northern areas. In the fall, they eat heavily to pack on fat, which will enable them to spend long stretches in their dens without eating. They may lose up to half their fat through the winter. Dense hair helps keep them warm, but a protective den is important for survival.

Habitat

The Raccoon’s preferred habitat is a wooded area near water, whether a marsh, swamp, bog, stream, or a backyard Koi pond. They avoid open spaces with no trees to climb if they’re in danger. However, being smart and adaptable, they’ve learned to survive where there are few trees by taking up residence in such places as storm drains, attics, chimneys, and under sheds.

Food sources

Raccoons are omnivorous and opportunistic. They eat whatever they can find—rodents, eggs, crayfish, frogs, fish, snakes, insects, nuts, vegetables, fruits, grains, small mammals, and, sometimes, roadkill. They’re a nuisance to farmers or gardeners when they raid poultry houses for eggs and chicks or damage crops. For urbanites, the biggest problem is keeping them out of trash containers–they love leftovers.

Nesting and cover

Raccoons spend the daytime resting where they’ll feel safe and sheltered. That may be in a brush pile, a hollow tree or log, an old squirrel’s nest, a culvert, an abandoned building, or an opening under a porch or shed. If they can find a way in, an attic or chimney will do just fine, too. They frequently move, sometimes daily, except for females when raising their young.

Reproduction

Male Raccoons become sexually mature at about two years, and females at one year. They mate once a year, between January and June. The male stays around for about a week after mating and then leaves in search of another female. Actually, he has no choice: if he tries to stay longer, she’ll chase him away.

Os penis and uterine horn

Raccoons have unusual genitalia. Males are among the few mammals with a penis bone (called a baculum or os penis). Experts aren’t sure of its function, but some hypothesize it’s to make the erect penis more rigid or to help stimulate the female. A small percentage of females have a tiny bone in their clitoris, called a baubellum or os clitoris. (Early humans also had these bones.)

Females have two ovaries and a “uterine horn” attached to each one. Embryos conceived from the eggs in one ovary migrate to the uterine horn of the opposite ovary, a process that allows room for more embryos. The babies are born, however, through a single vagina. Females typically have three pairs of mammary glands, sometimes four.

The pregnant female searches for a suitable den, one that’s sheltered and safe, and lines it with leaves. She usually delivers three or four babies, but up to seven is possible. The babies, called kits, have closed eyes, and their ears are pressed tight to their heads. They hardly have any hair, so the masked face and ringed tail are, for now, only a shadow. In about three weeks, their eyes open. By seven weeks, they’re fully furred. Then, at around nine weeks, they have their first taste of food other than milk as they start following their mother on her nightly forays. At about four months, they’re entirely weaned.

Family group

The family group stays together until late fall, with the youngsters learning all their mother’s sly know-how. Sometimes these families make quite a ruckus with their clamoring, trashcan-toppling ways. The mother is very protective of her kits, going so far as to boost them up trees if they’re threatened. Moreover, she’ll fight viciously to protect them.

As the weather turns cooler, the family eats, eats, eats. They need to pack on as much body weight as possible heading into winter—up to 30 percent more. Sometimes the kits stay with their mother until she’s forced to kick them out to make room for her next litter. Usually, though, they strike out in time to find a suitable winter den of their own. They may have to go miles away in their search, while their mother will carry on alone until the next season.

Life span

Raccoons can live up to 20 years in captivity, but in the wild, most die before their second year. If they survive that long, they live an average of five years.

Predators

The worst predator of Raccoons is humans. In Minnesota alone, hunters and trappers take over a quarter of the Raccoon population every year. In other areas, authorities control them by baiting or trapping them. Pelt hunters trap them because couturiers use their fur for sheared Raccoon coats. Many more die under the wheels of vehicles when they’re hit while feeding on roadkill. Other predators include Coyotes, foxes, large hawks, owls, wolves, and snakes.

Raccoon latrines

Raccoons like to create community latrines, places where they all go to defecate. Latrines may be located on any flat surface that’s situated off the ground, such as woodpiles, large rocks, roofs, and decks, although sometimes at the fork or base of a tree. Unfortunately, they may also use attics and other indoor spaces if accessible. Their feces are tube-shaped and about the diameter of a nickel or dime. Fresh feces are usually darker, but not always, and old waste is lighter in color.

The latrines are more than just unsettling and unsanitary piles of feces. They’re also hazardous because Raccoons are the primary host of a dangerous roundworm called Baylisascaris procyonis, which lives in the intestines. Its eggs are expelled in feces. If other animals, including humans, inadvertently ingest them, the hatched larvae travel through the body and cause severe damage to the eyes, brain, and spinal cord. Fortunately, roundworms in humans are rare—only 25 cases in the U.S. since 2003. Still, if you see a latrine in your yard, it’s a good idea to clean it up promptly. Especially if you have small children, who are more likely to put contaminated fingers or objects into their mouths. Pets, too, should be kept away from the latrine. It’s essential to be careful when cleaning one up. Indoor latrines are particularly hazardous, and it’s best to leave the cleanup to a professional.

Raccoon and rabies

The disease that most commonly kills Raccoons is a virus called distemper. But a small percentage are found to have rabies, another virus lethal to them, and humans, as well. “Rabies” (a singular noun, even though there’s an ‘s’ at the end) is carried in saliva and transmitted through biting. Only 1,499 Raccoons nationwide were diagnosed with rabies in 2018 (the most recent report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). So, you can see that the percentage of infected Raccoons is quite low within a population of animals that inhabits nearly the entire country.

Symptoms of rabies include a sickly appearance, loss of coordination, and being abnormally vocal. A few have no noticeable symptoms at all. Should you observe abnormal behavior, call your local Animal Control Office. Always stay away from wild animals, even cute baby ones. If you’re bitten, whether you believe a Raccoon is rabid or not, immediately see your doctor for rabies shots for yourself—that’s the only way to save your life.

¹The others are the Crab-eating Raccoon, Procyon cancrivorus, of Panama and Central America and the critically endangered Cozumel Raccoon, Procyon pygmaeus, of Cozumel Island (off Mexico).

More reading:

Sleeping winter away

Summer wildlife disappears in winter, but where to?

Frequent questions about Northern Raccoons