You may have heard that earwigs creep into the ears of sleeping people and burrow into their brains to lay eggs. Well, that’s just horrifying—and fortunately not true, or we’d be recommending earplugs! That myth has been around since the Middle Ages when earwigs were first labored with that unfortunate name. To prove it wrong, entomologist May Berenbaum,1 recipient of the 2014 National Medal of Science, examined about ten centuries of literature and found only one report of an earwig actually crawling into a human’s ear. They can be startling to encounter because of their prominent pincers, but the truth is that earwigs are harmless to humans, and you’ll be surprised as you read about how interesting they are. Here’s a for-instance: they have intricately folding wings, pincers that a carpenter would admire, and, get this—they’re doting mothers! And there’s more.

Some background

Earwigs belong to Dermaptera (der-MAP-ter-uh), a small order of about two thousand species. “Dermaptera” comes from the Greek dermatos for skin and pteron for wing, referencing their leathery forewings. “Earwig” is from the Old English ēare, which means “ear,” and wicga, which means “insect.”

The oldest earwig fossil is about 208 million years old, which takes it back to the Triassic Period, during the time of dinosaurs. The earwigs of today can be found around the world, except in Antarctica, but they are most common in the tropics. About twenty-three species inhabit the United States.

The smallest species in the world is Eugerax peocilium, which is about 0.12 inches (3 mm) long; most are around 0.4 to 0.8 inches (10–20 mm). The largest is the Australian Giant Earwig, Titanolabis colossea, which grows to an unnerving 2.0 inches (50 mm). In 2014, an even larger species, the St. Helena Giant Earwig (Labidura herculeana), was declared extinct due to habitat loss on its island home.

Earwigs cause minimal damage to plants and may even be beneficial as recyclers of decaying material and predators of nuisance insects.

Physical description

Like all other insects, earwigs have three body sections: head, thorax, and abdomen, and are covered by an exoskeleton that provides support and protection. Their body is long and somewhat flattened, which allows them to fit into the tight spaces they prefer. Their colors run from light brown to black.

Head

Earwigs have two eyes, two thin, bead-like antennae, and mouthparts designed for chewing. The brain mainly contains clusters of neurons that interpret sensory information sent to it from eyes, taste, and smell receptors. It doesn’t play a significant role in bodily functions; ganglia throughout the rest of the body primarily handle those.

Recent research indicates that insects can have consciousness and ego.3 Researcher Julia Deiters, who has studied earwigs for years, would agree with that—she says they display some human-like traits, such as elaborate courtships and unique personalities.4

The eyes are compound, composed of hundreds of individual lenses that transmit signals through neurons to the brain, which interprets them. The mouthparts include a labrum and labium (upper and lower lips), maxillae (upper jaw), and mandibles (lower jaws).

Thorax

The thorax is the middle section of the body. Attached to it are six legs and four wings. The legs are short to moderately long, depending on the species, and adapted for running. Earwigs aren’t good fliers, so they compensate by being fast on their feet.

Intricate folding wings

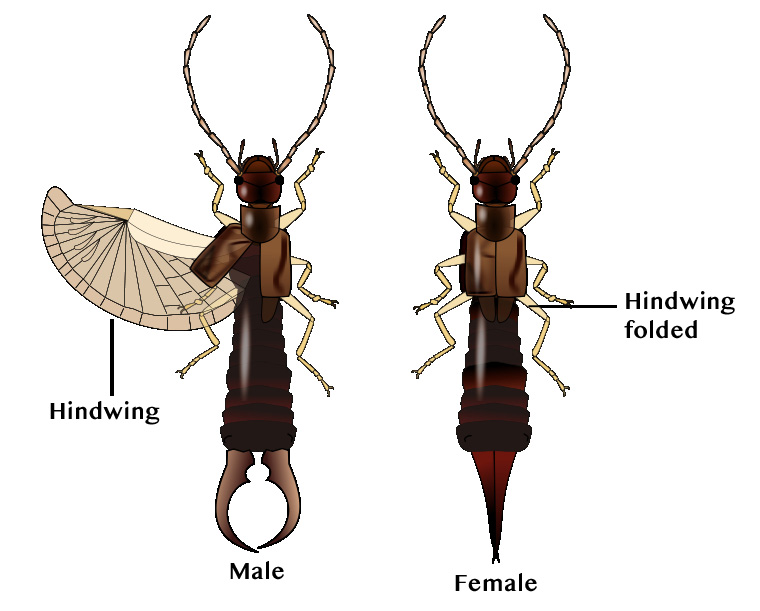

While some earwig species lack wings, most have them, and it’s their most interesting feature. Not the forewings, in particular, which are short, leathery, and modified into covers for the hind wings, like the hardened elytra of beetles, and aren’t used for flight.

It’s the hind wings that amaze. They’re shimmery, semi-circular, and kept so intricately folded under the forewings that when they unfold for flight, they expand to ten times their size. The way they fold is unique: First, they fold lengthwise, like a fan, and then crosswise. Lastly, the earwig curls its abdomen and uses its pincers to tuck in a remaining little bit of exposed wing. The wings have stretchy joints that lock in place without any activation of muscles, whether they’re folded or unfolded.5

Science writer Grant Allen6 described the process this way:

“. . . the second pair, or true wings, are flat and papery behind, but have a curious horny rib or “stiffener” in their front portion. This stiffener acts exactly like the whalebone or steel in a pair of corsets, or like the ribs in an umbrella. The beautiful folds and creases in the true wings resemble those in a fan or Japanese parasol, but they run two ways, some lengthwise, and some transversely. They are exquisitely true in their wrinkles, and enable the insect to shut up the wing with perfect accuracy.”

Abdomen

The abdomen is the back section of the body and the largest. It’s cylindrical and long and consists of ten segments. Within it are the rearmost parts of the nervous, digestive, and circulatory systems, in addition to the excretory and reproductive systems. Also, the pincers that we find so alarming. Some species also have glands that can shoot a foul fluid up to 4 inches (10 cm) away as a method of defense.

The abdomen is filled with “blood” (hemolymph), which is clear because it doesn’t contain iron, which is what creates the red-colored blood of mammals. Another contrast is that the circulatory system doesn’t carry oxygen. Instead, earwigs breathe through a series of fourteen holes (spiracles) spaced along their abdomen, seven on each side (another six are in the thorax). A trachea connects to each spiracle and networks throughout the body to deliver oxygen to cells and collect carbon dioxide to be expelled.

Pincers

At the tip of their abdomen, earwigs have two projections commonly called pincers but are technically cerci (SIR-sigh). They may be what you notice first about this insect because they’re pretty intimidating. Caliper-shaped and made of chitin (same as the exoskeleton), they’re used to help fold the hind wings, capture prey, and defend against predators. When showing aggression or alarm, earwigs bend their abdomen and hold the pincers over their head in a scorpion-like manner.

The female’s pair is straighter than the male’s, but for both sexes, they look dangerous, and you should take that as a warning! If an earwig is handled carelessly, it might pinch you (it’s painful but not severe). Otherwise, these insects are harmless to humans. (There are other species with cerci, but only earwigs have heavy, caliper-shaped ones.)

Life cycle

Earwigs undergo incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetabolism), which means they go through three life stages: egg, nymph, and adult.

Males and females mate in the fall, then remain together in a nest located under debris or in crevices or soil. Sometime in mid-winter to early spring, the male takes his leave. The female then lays fifty to eighty eggs. Depending on the species, she has one or two broods each season. The young, called nymphs, hatch in about seven days and make their egg case, which contains nutrients, their first meal.

Earwig mother in her nest tending to her young nymphs and eggs (Tom Oates, 2010/ Wiki; CC BY-SA 3.0)

The mother takes care of her babies, a highly unusual behavior in nonsocial insects. If her eggs get dispersed, she rushes to save them and puts them back in the burrow. She keeps them clean by eating any parasites and fungi on them. After they hatch, she’s a caterer who brings them food until they’re ready to be on their own.

The nymphs look something like adults, but they’re smaller, wingless, and pale. They shed (molt) their outer skin four or five times as they eat and grow larger. With each molt, the wings get bigger and the antennae longer.

The amount of time the nymphs stay in the nest varies with the species, but they begin foraging on their own by the end of their second molt. They mature to winged, sexually mature adults in around fifty days. By that time, they also have their adult coloration. In an ironic, tragic twist to this story, after taking such tender care of her young, the mother is apt to eat those who overstay their welcome! Earwigs live for about a year from the time they hatch.

Food sources

Earwigs are omnivorous. Most species feed on plant material—fungi, algae, mosses, pollen, flowers—or are scavengers on dead and dying vegetation. Some occasionally prey on small insects like aphids and mites.

Where to find earwigs

Unless you go looking for them, you may never see an earwig. Although they might come out in the daytime, they’re nocturnal and primarily hide. They like dark, moist places, so to find them, look under stones, boards, mulch, dead leaves, logs, and flowerpots. You might also find them in rotting wood, where some feed on the decomposing plant matter. At night, look for them around lights or lighted windows.

An earwig might find its way into your house. That usually happens accidentally when they ride in as hitchhikers on cut flowers or other items. They can become indoor pests if they invade in large numbers during prolonged heat and drought when they seek moisture and a cooler environment. Earwigs need to eat, so your houseplants and food items will be on their menu. To eliminate them, carefully sweep or pick them up and put them outside. Take care not to crush them as it releases an obnoxious odor—and don’t get pinched!

| 1 About May Berenbaum |

| 2 Video: Earwig, Forficula auricularia (zaphad1 / Flickr; CC BY-SA 3.0) |

| 3 Jason Daley, “Do Insects Have Consciousness and Ego?,” SmithsonianMag.com, April 19, 2016. |

| 4 Douglas Main, “Animals Weird & Wild,” NationalGeographic.com, November 13, 2018, https://bit.ly/4anTwTY. |

| 5 R. Ishiguro, T. Kawasetsu, Y. Mortoori, J. Paik, K. Hosoda, “Earwig-inspired foldable origami wing for micro air vehicle gliding,” Frontiers.org, November, 2023. |

| 6 Allen, Grant. 1898. Flashlights on nature. New York: Doubleday & McClure. |

More reading:

All about honeybees

True bugs: the good, the bad, the ugly

Learn more about insect anatomy