Background • Physical characteristics, Senses • Intelligence • Shell, Scutes • Reproduction, Eggs, Sexes • Lifespan, Behavior, Communication, Hibernation • Foods, Habitat, Predators, Environmental threats • How we can help turtles

Who won the race—the tortoise or the hare? Most of us know the tortoise won in Greek storyteller Aesop’s famous fable, but why isn’t it a “turtle” that won or even a “terrapin?” These three terms are used for the same animal, but to experts, there’s a distinct difference between turtle, tortoise, and terrapin.

In the United States, environmentalists and scientists make a distinction between turtles that live in the sea (called turtles or sea turtles), turtles that live on land (called turtles or tortoises), and turtles that are semi-aquatic or prefer brackish water (called terrapins). Some other parts of the world use these terms differently. For instance, in Australia, only sea turtles are called turtles; all others are tortoises. In Britain, land turtles are always tortoises, saltwater species are turtles, and freshwater species are terrapins.

When experts want to refer to the three groups as a whole, they call them chelonians after the name of their taxonomic superorder, Chelonia (kell-OWN-ee-uh). “Chelonia” comes from the Greek word chelone, meaning tortoise, but “turtle” originates from Old English turtla and Latin turtur. “Terrapin” is from Algonquin torope.

Background

Turtles are reptiles in the same scientific class, Reptilia, as crocodiles, alligators, lizards, worm lizards, snakes, caimans, and the Gharial and Tuatara, and are in the order Testudines (tes-TUDE-uh-neez). Based on a fossil found in 2008, they’ve existed for 200 to 250 million years, which places them back in the Triassic Period when the first dinosaurs appeared. The oldest box turtle fossils, about fifteen million years old (Miocene Epoch), were found in Nebraska; they are basically the same as today’s. Today, 357 species and 129 subspecies inhabit the world on all continents except Antarctica. The U.S. has more than any other country, 57 native species.

Box Turtles, which are in the family Emydidae and genus Terrapene, are probably the best-known in the U.S. Native to the U.S. and Mexico, they consist of seven species and seven subspecies separated into two groups: common box turtles and ornate box turtles. The Common Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina, and its five subspecies are the most widely distributed, inhabiting south-central, east and southeast regions, and Mexico. The Ornate Box Turtle, Terrapene ornata, and its two subspecies inhabit the south-central and southwestern U.S. and Mexico.

Physical characteristics

Adult box turtles typically range in size from 4 to 7 inches (10.2–17.8 cm) across the carapace, depending on the species, and weigh up to 2.0 pounds (0.9 kg).

Male or female?

It can be a bit hard to tell males and females apart. Females are sometimes larger than males, shell patterning is similar, and the sex organs are hidden inside the shells. But there are a few clues.

- Females have a highly domed shell, while males’ are slightly flatter on top. Males also have a slightly concave bottom shell.

- The shell, face, and foreleg colors on males may be brighter than on females.

- Often, but not always, a male’s irises are red or orange, and a female’s are brown or yellow.

- Males have a claw on each hind foot that curves inward.

- Both males and females have an opening in their tail, called a vent, but males have a long, thick tail with a vent located farther away from the back edge of the shell.

- Females have a short, skinny tail, and the vent is closer to their shell.

Head, senses

The turtle’s eyes are slightly on the side of the head and positioned to look downward, more toward the ground (some aquatic turtles have eyes placed to look upward.) They have superior eyesight, including color vision—not just in the daytime, but also at night—although their shell interferes with their peripheral vision.

The nose, positioned just above the mouth, has two nostrils and is easy to see. Turtles have an excellent sense of smell, which they use to help them find food, mates, and territory. Their upper and lower jaws are hard and covered by sharp, horny ridges used to chew the tough, fibrous vegetation they eat. The upper jaw forms a beak with a hook at the center. They have a sense of taste, but it isn’t known how sensitive it is. They also have a sense of touch; they can feel even in their shell.

Turtles don’t have external ears. Instead, a layer of skin on each side of the head, well behind the eyes, forms a tympanic membrane and protects the middle and inner ears. Their hearing is in the low-frequency 50 to 1,500 kilohertz range, which is very limited. (By comparison, a human’s is 20 to 20,000 kilohertz.) So, while they do hear some sounds, scientists speculate their ears may be used mainly for balance. Also, many of the deep sound waves they can hear happen to cause ground and water vibrations, which they know how to interpret.

Intelligence

Yes, turtles have a brain, and you may wonder if there’s any intelligence in it. No reports specifically address box turtle intelligence, but tests of wood turtles, Glyptemys insculpta, have shown they’re as good as rats at finding their way through mazes.1 Clever tests on “Moses,” a male Red-footed Tortoise, Chelonoidis carbonaria, showed he used memory and intelligent planning rather than smell to find food in a maze.2 And, another study of Red-footed Tortoises confirmed they have good long-term memory.3 So, why wouldn’t box turtles be equally smart?

People who keep them as pets say they’re sociable. They recognize their owner’s appearance and voice. They know to go to their food bowl when they see a human approach. One owner reports that her turtles rattle small stones in their food bowl if they aren’t fed on time. Some say their box turtles like to be held, enjoy swimming in kiddie pools, roam around, dig in the dirt, and enjoy sampling different foods. They can also be playful. Watch one play with a ball and a dog.

Neck

Taxonomists have divided turtles into two suborders, Cryptodira and Pleurodira,4 based primarily on how they fold their long, flexible necks. Box turtles belong to Cryptodira, the hidden-necked turtles because their method of retraction is to pull it straight back into their shell rather than fold it sideways as the other group does.

Legs

Box turtles have legs that are short, stout, and round, with broad feet and slightly webbed toes with long claws designed for digging and ripping into food. The number of toes can vary; for example, Three-toed Box Turtles, Terrapene triunguis, have three toes on the front and four on the back, Eastern Box Turtles have five toes on the front and four on the back, and Ornate Box Turtles have five toes on the front and four, but sometimes only three, toes on their back feet.

You’ve undoubtedly noticed that turtles don’t run—they amble. They’re capable of bursts of “speed,” but that just means walking a little faster. People who enter them in turtle races make various claims about speed, but their measure of speed is in feet per hour (one foot is thirty centimeters).

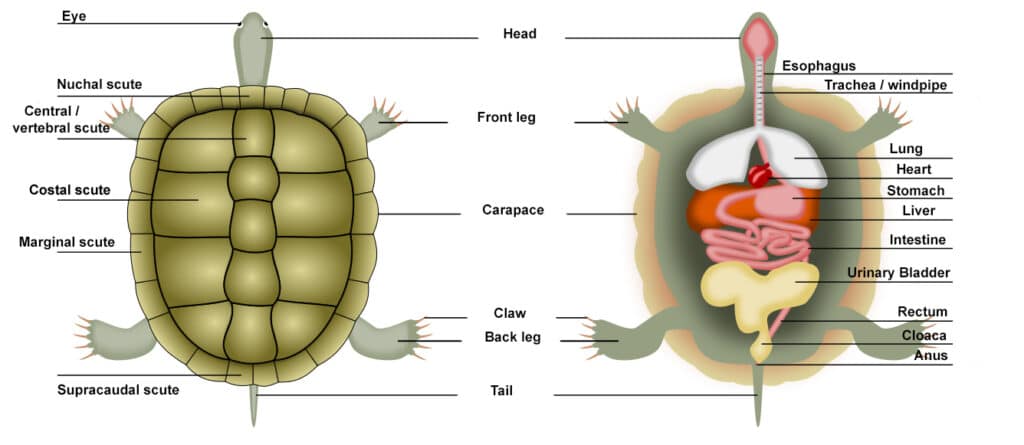

Internal organs

Internally, box turtles differ from humans and other mammals in several ways. First of all, they have a three-chambered heart instead of four. Their blood flows from the hind limbs into the kidneys through the renal veins, while in mammals, it moves out of the kidneys through those veins.

They breathe differently, too. Their lungs are large and located above all the other organs. Where a mammal’s ribs move in and out with each breath, the turtle’s are fixed in place. To compensate, turtles have thin muscles that compress and relax the lungs to move air in and out.

However, the digestive system is similar to that of most other vertebrates (animals with a backbone). The two main parts are the stomach and the intestines. The digestive system ends at the cloaca (klo-A-kuh), through which solid waste passes to the “anal vent,” located partway down the tail.

Shell

“Box” turtles are named for their ability to withdraw their head, tail, and legs into their shell and tightly close their “door.” The shell is permanent, a part of their skeleton—they can’t shrug it off or crawl out of it. It’s a vital part of their anatomy, an armor against predators, a shield against extremes of heat and dryness, and, sometimes, from a fire. It has three parts. Watch how tightly it closes against predators.

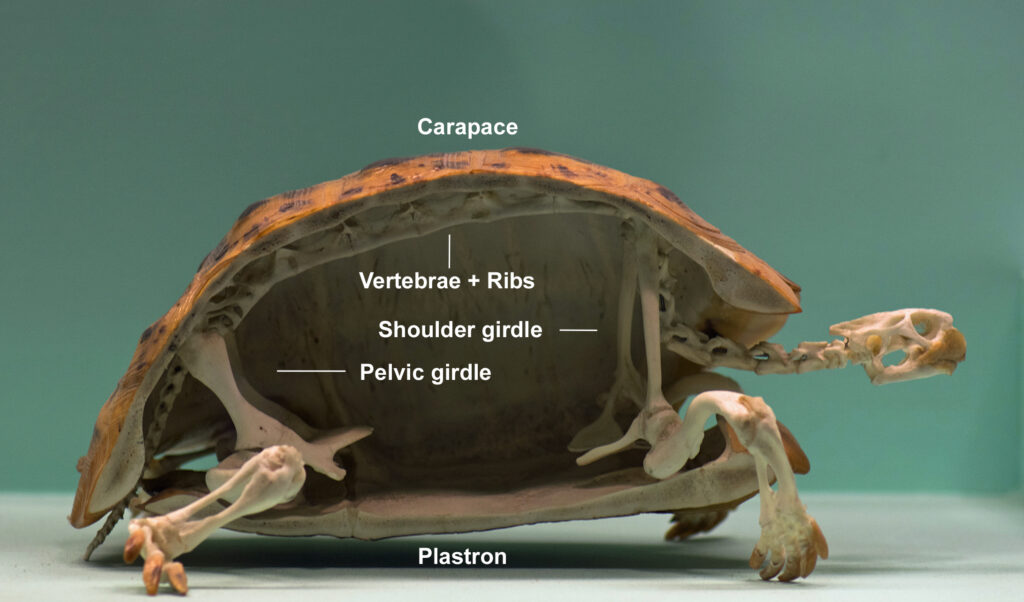

1. Carapace (CARE-uh-pace)

The top shell. The inner part of it is composed of about fifty bones, including the ribs and vertebrae, plus cartilage. All this forms the domed shape of the shell.

Scutes on the carapace of a Florida Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina bauri (Jonathan Zander [Digon3] / Wiki; CC BY-SA 3.0)

The carapace is very hard but isn’t impervious to pain and pressure. It contains nerve endings, and just as humans can feel through their fingernails, turtles can feel touch through their shell. (Their leathery-looking skin is very sensitive, too.)

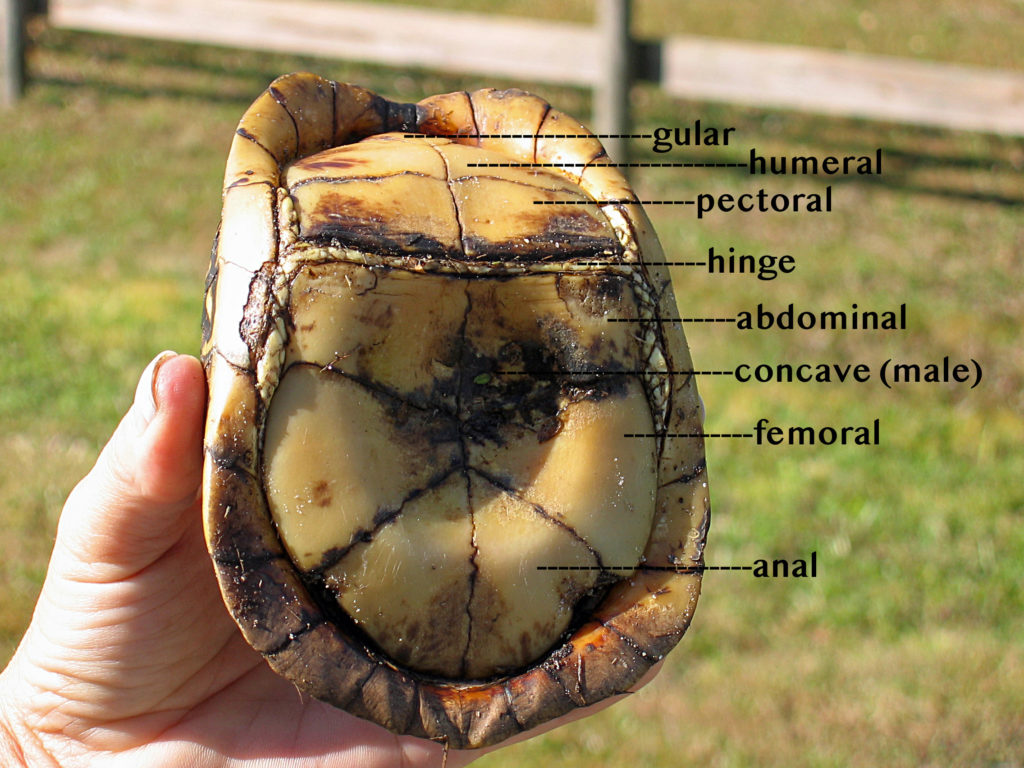

2. Plastron (PLASS-tron)

The bottom shell. It consists of the clavicles (shoulder blades), the bones between the clavicle, and portions of the ribs. The plastron of females is relatively flat. Males generally have a more concave one, presumably for easier mating.

Plastron of a box turtle. Notice the hinge which has allowed the turtle to tightly close its “door.” The center is concave, indicating there’s a male within. (Ineta McParland / Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

The plastron has a hinged joint between the abdominal and pectoral scutes (or scales), which allows it to close tightly after the turtle pulls its head, legs, and tail inside. (Not all chelonian species can do this. Mud turtles, for example, can only close the front, hinge-back turtles can only close the rear, and sea turtles and snapping turtles can’t close their shell at all.)

3. Bridge

The bridge is a bony structure that runs between the top and bottom shells, from behind the forelegs to the front of the back legs, on each side of the turtle. It joins the carapace and plastron together.

The ribs and other bones forming the shell’s shape have three layers covering them. First is a layer of numerous membranous bones called thecals (THEE-calls). The thecals are covered with a layer of osteoderms (or epithecals), which are fused plates of bone. The final layer is made up of scutes, the turtle’s “skin.”

Scutes

Scutes (which are made of beta-keratin like our fingernails) roughly correspond to the position of the turtle’s bones and body parts and are scattered to help give the shell more rigidity. They don’t overlap. There are thirty-eight on the carapace and twelve to sixteen on the plastron.

Scutes also provide the patterns and colors of the shell. Different species have different patterns and designs, and some variances exist between individuals of the same species. The colors and patterns of box turtles help them blend into their environment.

The shell grows throughout the turtle’s life and develops growth rings. If injured, it can regenerate—keratin slowly grows beneath the afflicted area, and eventually, the damage falls off.

The box turtle’s vertebrae are elongated and rigid in the central part of the shell but small and flexible in the neck and tail, allowing for easy movements there.

Reproduction

Courtship typically occurs in the spring. But, sometimes, other seasons, too, if a male and female happen to encounter each other. Sources differ on when box turtles reach sexual maturity. Some say it’s at four or five years of age, while various others report it to be somewhere between that and twenty years. At any rate, when the time comes, the turtles find each other through scent and sight. Males will fight over a female by shoving, butting, biting, and flipping a competitor onto his back.

Their sex organs are located in the cloaca. Courtship begins with the male circling and shoving the female and biting her carapace. Eventually, he grips the back of the female’s shell with his hind feet and positions himself over her to mate. If she’s receptive, she’ll use her hind legs to help him grasp. His penis is long, so at this point, the male leans back nearly to vertical, with the back edge of his carapace touching the ground while they’re joined together. There’s no guarantee the turtles will find a mate every year, but not to worry, females can store sperm for up to four years! Watch an awkward courtship and an overturned box turtle right himself.

Eggs

Sometime in late spring to mid-summer, the female digs a hole in sandy or loamy soil, lays her eggs (usually four to six, called a clutch), then covers them up and goes away. Females inhabiting southern areas may have more than one clutch per year. The eggs are left on their own; their mother never returns to them or her hatchlings.

Incubation, male-female determination

Incubation takes seventy to ninety days. Unlike humans and other mammals, the embryos lack sex chromosomes that would turn them into males and females. The sex they’ll become falls to the vagaries of the ambient temperature around them (especially during a critical stage of embryonic development) through a process called Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination. Here’s what happens: The ideal range of temperature for, say, incubating the eggs of the Eastern Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina, is between 72°F and 93°F (22°C to 34°C). Those eggs that incubate in the lower range produce males. Higher temperatures produce females. Eggs incubating mid-range have a 50-50 chance of being male or female.

Embryonic development

While developing inside the shell, the embryos are attached to a yolk sac by something like a human’s umbilical cord. The yolk is vital—it’s the nourishment they need for growth. When the time comes to exit their hard shell, the hatchlings use what’s called an egg tooth. The egg tooth is a hard, sharp protuberance located at the tip of the upper beak. It will fall off in a few days, but for now, the little turtles will use it to peck their way through the shell. It’s a hard job and can take from a few hours up to two or three days. When they hatch, the turtles are still attached to their yolk sac, but the last of its contents rapidly absorbs into the hatchling’s abdomen, and they can live on it for several weeks.

Baby Eastern Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina, with cord and egg sac attached (Nolan Eggert / iNaturalist; CC BY-NC 3.0)

As you can imagine, the tiny turtles are vulnerable. Their carapace is somewhat pliable, and the hinge doesn’t function until their ribs fuse over time. They’ll spend most of their time hiding and feeding on any small prey they find. If they can survive the four to five risk-filled years it takes for their hinge to develop, their shell will become nearly impregnable. Plus, they can protect themselves by closing up inside it.

Lifespan

If they make it to adulthood, box turtles have an average life expectancy of about fifty years. Some have lived to be over a hundred years of age.

Behavior

Box turtles are diurnal, meaning they’re active in the daytime, although most active at dawn and dusk. Their days are spent foraging, eating, and sometimes mating. Like all reptiles, they’re ectothermic—they can’t regulate their body temperature, and it’s, therefore, affected by the temperature of their surrounding environment. They don’t like to overheat and usually stay in the shade of plants to remain cooler, especially in the hottest part of the day. In warmer months, they’re often found near water, probably to stay cooler. Those that live in desert areas burrow underground to keep cool.

Communication

Box turtles can vocalize, but they don’t do it often. They may call to find mates or while mating. There are reports that baby box turtles will vocalize to get attention. Distressed or ill turtles may make sounds. Turtles may also make a hissing noise, but it’s produced by how they breathe. Listen to a box turtle’s trill.

Hibernation (brumation)

Box turtles in colder areas “hibernate” from fall to spring. This is the more widely used term for their period of dormancy, but technically, they experience brumation, which differs in the metabolic processes involved. They do several things to prepare for it. They stop eating to empty their digestive system. Usually, they move into wooded areas and edges—sometimes traveling several hundred feet from their summer grounds. There, they burrow down into loose soil or under decaying vegetation, sometimes in the same place year after year. Several may brumate together. Their heart rate slows from about forty beats per minute to about one every five to ten minutes.

If the ground is soft enough, the turtles may dig deeper and deeper as temperatures fall closer to freezing. Then, when spring arrives, and temperatures rise, the turtles begin to slowly move upward.

Food sources

Box turtles are opportunistic omnivores and eat whatever is available. They especially like earthworms, snails, beetles, caterpillars, fallen fruit, flowers, leafy plants, and grasses. They sometimes eat carrion. The Desert Box Turtle, Terrapene ornata luteola, includes cactus in its diet.

Habitat

Box turtles are mainly terrestrial and tolerant of most habitats, including open woodlands, forests with moist, well-drained soil, thickets, grasslands, and even semi-arid areas.

Predators, environmental hazards

Young turtles, whose shells are not yet hardened, are the most seriously threatened by predation. Common predators are minks, skunks, raccoons, large birds, and rodents.

Box turtles should be flourishing in urban areas. City yards offer everything they need—bog gardens, vegetable gardens, shade and fruit trees, insects, snails, worms, and hiding places. However, habitat destruction, automobiles, and illegal poaching for the pet trade are a constant threat. Habitat fragmentation caused by urban development is preventing many from locating mates, so they’re living out their lives without reproducing.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature says in its 2021 report5 that 62.4 percent of all turtle species are classified as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered.

What we can do to help all turtles

The Maryland Zoo lists these steps to help protect turtles.

- Never remove a turtle from the wild.

- Never relocate a turtle in the wild unless you see one trying to cross a road. Help a turtle cross a road only if you can do it safely, and be sure to point it in the same direction that it was headed.

- Never return a pet or rescued turtle to the wild without first contacting your state’s Department of Natural Resources.

- Educate friends and family about the importance of observing turtles in the wild but not touching, disturbing, or collecting.

- When visiting wetlands, tread lightly and stay on designated paths.

- Use pesticides and other hazardous materials sparingly and dispose of them properly to ensure they do not end up in waterways.

- Recycle to reduce waste and reduce the need for landfills.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

1 James Harding, “Glyptemys insculpta, North American Wood Turtle,” AnimalDiversityWeb.org, https://bit.ly/3RrYTus. 2 Jeff Hecht, “Cold-blooded cognition: Tortoises quick on the uptake,” NewScientist.com, December 20, 2011, https://bit.ly/3rdcxXJ. 3 Cheyenne MacDonald, “Tortoises never forget: Researchers find animals still remember the best places they found food 18 months later,” DailyMail.com, February 1, 2017, https://bit.ly/3ENO2U5. 4 Pleurodira, or “side-necked” chelonians, fold their neck sideways and tuck their head near their shoulder under the edge of the shell for protection. They’re mainly freshwater turtles of the Southern Hemisphere. 5 International Union for Conservation of Nature, “Turtles of the World Checklist,” https://bit.ly/46khFIs. More reading:

Where does wildlife go over the winter?

Wild animals don’t make good pets

Turtles: frequent questions

‘The Evolution of the Turtle’s Shell: It Wasn’t for Protection‘

Reptiles

In your yard: garter snakes

More interesting facts about snakes